ORNL Researchers Make Scalable Arrays of "˜Building Blocks' for Ultrathin Electronics

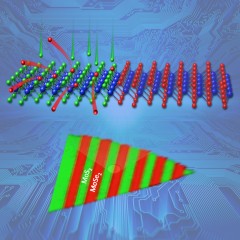

CAPTION/CREDIT: Complex, scalable arrays of semiconductor heterojunctions"”promising building blocks for future electronics"”were formed within a two-dimensional crystalline monolayer of molybdenum deselenide by converting lithographically exposed regions to molybdenum disulfide using pulsed laser deposition of sulfur atoms. Sulfur atoms (green) replaced selenium atoms (red) in lithographically exposed regions (top) as shown by Raman spectroscopic mapping (bottom). Image credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Dept. of Energy

Complex, scalable arrays of semiconductor heterojunctions"”promising building blocks for future electronics"”were formed within a two-dimensional crystalline monolayer of molybdenum deselenide by converting lithographically exposed regions to molybdenum disulfide using pulsed laser deposition of sulfur atoms. Sulfur atoms (green) replaced selenium atoms (red) in lithographically exposed regions (top) as shown by Raman spectroscopic mapping (bottom).

Semiconductors, metals and insulators must be integrated to make the transistors that are the electronic building blocks of your smartphone, computer and other microchip-enabled devices. Today's transistors are miniscule"”a mere 10 nanometers wide"”and formed from three-dimensional (3D) crystals.

But a disruptive new technology looms that uses two-dimensional (2D) crystals, just 1 nanometer thick, to enable ultrathin electronics. Scientists worldwide are investigating 2D crystals made from common layered materials to constrain electron transport within just two dimensions. Researchers had previously found ways to lithographically pattern single layers of carbon atoms called graphene into ribbon-like "wires" complete with insulation provided by a similar layer of boron nitride. But until now they have lacked synthesis and processing methods to lithographically pattern junctions between two different semiconductors within a single nanometer-thick layer to form transistors, the building blocks of ultrathin electronic devices.

Now for the first time, researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have combined a novel synthesis process with commercial electron-beam lithography techniques to produce arrays of semiconductor junctions in arbitrary patterns within a single, nanometer-thick semiconductor crystal. The process relies upon transforming patterned regions of one existing, single-layer crystal into another. The researchers first grew single, nanometer-thick layers of molybdenum diselenide crystals on substrates and then deposited protective patterns of silicon oxide using standard lithography techniques. Then they bombarded the exposed regions of the crystals with a laser-generated beam of sulfur atoms. The sulfur atoms replaced the selenium atoms in the crystals to form molybdenum disulfide, which has a nearly identical crystal structure. The two semiconductor crystals formed sharp junctions, the desired building blocks of electronics. Nature Communications reports the accomplishment.

"We can literally make any kind of pattern that we want," said Masoud Mahjouri-Samani, who co-led the study with David Geohegan. Geohegan, head of ORNL's Nanomaterials Synthesis and Functional Assembly Group at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, is the principal investigator of a Department of Energy basic science project focusing on the growth mechanisms and controlled synthesis of nanomaterials. Millions of 2D building blocks with numerous patterns may be made concurrently, Mahjouri-Samani added. In the future, it might be possible to produce different patterns on the top and bottom of a sheet. Further complexity could be introduced by layering sheets with different patterns.

Added Geohegan, "The development of a scalable, easily implemented process to lithographically pattern and easily form lateral semiconducting heterojunctions within two-dimensional crystals fulfills a critical need for "˜building blocks' to enable next-generation ultrathin devices for applications ranging from flexible consumer electronics to solar energy."

Tuning the bandgap

"We chose pulsed laser deposition of sulfur because of the digital control it gives you over the flux of the material that comes to the surface," said Mahjouri-Samani. "You can basically make any kind of intermediate alloy. You can just replace, say, 20 percent of the selenium with sulfur, or 30 percent, or 50 percent." Added Geohegan, "Pulsed laser deposition also lets the kinetic energy of the sulfur atoms be tuned, allowing you to explore a wider range of processing conditions."

It is important that by controlling the ratio of sulfur to selenium within the crystal, the researchers can tune the bandgap of the semiconductors, an attribute that determines electronic and optical properties. To make optoelectronic devices such as electroluminescent displays, microchip fabricators integrate semiconductors with different bandgaps. For example, molybdenum disulfide's bandgap is greater than molybdenum diselenide's. Applying voltage to a crystal containing both semiconductors causes electrons and "holes" (positive charges created when electrons vacate) to move from molybdenum disulfide into molybdenum diselenide and recombine to emit light at the bandgap of molybdenum diselenide. For that reason, engineering the bandgaps of monolayer systems can allow the generation of light with many different colors, as well as enable other applications such as transistors and sensors, Mahjouri-Samani said.

Next the researchers will see if their pulsed laser vaporization and conversion method will work with atoms other than sulfur and selenium. "We're trying to make more complex systems in a 2D plane"”integrate more ingredients, put in different building blocks"”because at the end of the day, a complete working device needs different semiconductors and metals and insulators," Mahjouri-Samani said.

To understand the process of converting one nanometer-thick crystal into another, the researchers used powerful electron microscopy capabilities available at ORNL, notably atomic-resolution Z-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy, which was developed at the lab and is now available to scientists worldwide using the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences. Employing this technique, electron microscopists Andrew Lupini and visiting scientist Leonardo Basile imaged hexagonal networks of individual columns of atoms in the nanometer-thick molybdenum diselenide and molybdenum disulfide crystals.

"We could directly distinguish between sulfur and selenium atoms by their intensities in the image," Lupini said. "These images and electron energy loss spectroscopy allowed the team to characterize the semiconductor heterojunction with atomic precision."

The title of the paper is "Patterned Arrays of Lateral Heterojunctions within Monolayer Two-Dimensional Semiconductors."

The research was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science. A portion of the work was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, a DOE Office of Science User Facility at ORNL. Basile received support from the National Secretariat of Higher Education, Science, Technology and Innovation of Ecuador.