How semiconductors can save the environment

The annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP) has always taken a keen interest in sustainable technology. As the global climate crisis becomes ever more pressing, a study by McKinsey has concluded that widespread commitment is required if the planet is to restrict global temperature rises to a 1.5°C trajectory by 2030. By Mark Lippett, CEO, XMOS.

With this in mind, technology – and the chips within – became a key area of focus in 2022, and 2023 looks set to see more of the same. Realising more sustainable methods of semiconductor manufacture and on-device energy conservation would represent major progress towards our shared temperature goal.

There’s economic incentive for the countries that get it right, too. Environmental activists can take heart from the race between the US, EU and China to lead on the development of green technologies – while their interests may be business-oriented, competition here is a catalyst for progress.

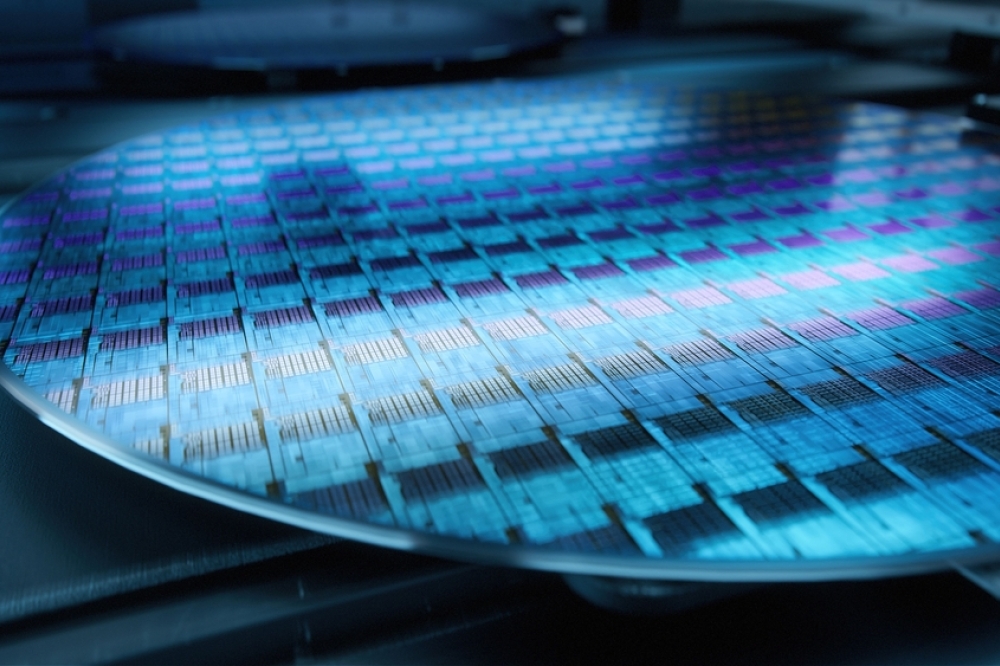

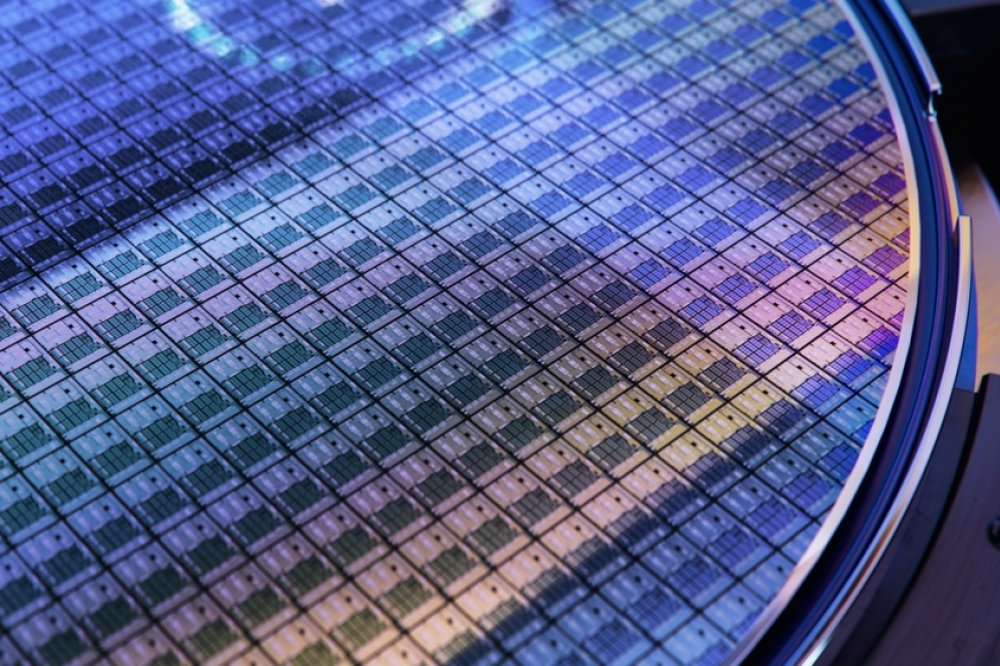

Production challenges

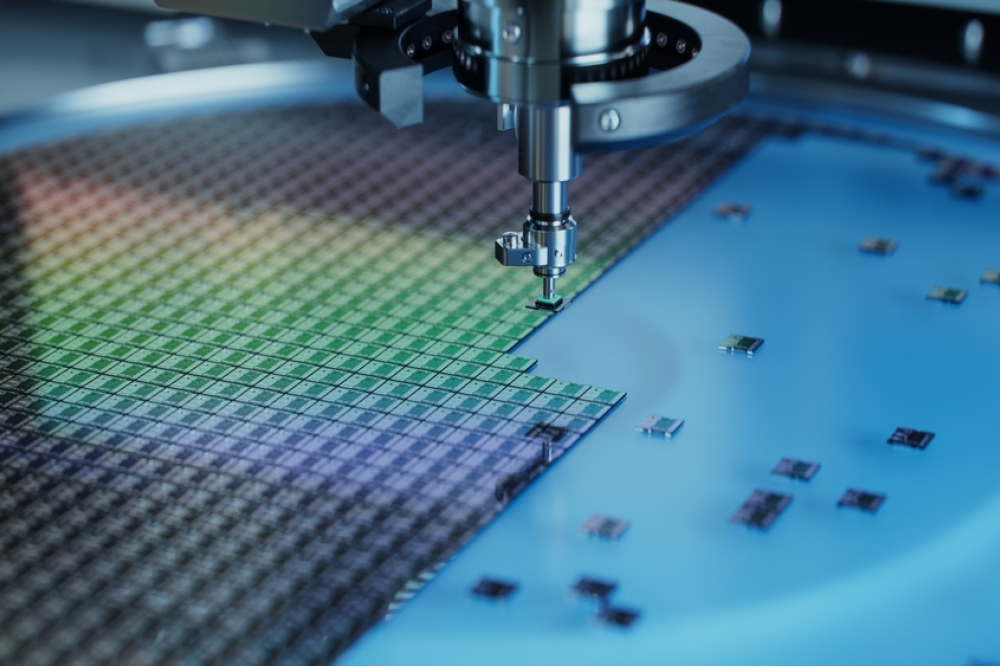

As a result of such circumstances, the Semiconductor Climate Consortium (SCC) was established last year. Formed of 60 leading industry organisations, the group attended COP27 in Egypt to present its sustainability strategy – including alignment on technology innovations within the supply chain to decrease emissions, with an aim to eliminate emissions entirely by 2050.

As with all production processes, semiconductor manufacture impacts more than the immediate production environment – from extraction of raw materials to transportation of finished goods.

Research from McKinsey has quantified emissions caused by semiconductor production based on the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol. Most either result from manufacturing processes within fabs (35%); or in heating/electricity/cooling appliances (45%), with the use of chips within devices making up the remaining 20%.

While the refinement of production processes is obviously very important, it also depends at least partially on the supply chain – reducing storage costs, producing the right amounts, and so on. As academics from the University of Stuttgart put it, planners must contend with “the overlapping of short-term supply chain disruptions with long-term structural features of the semiconductor industry”. For example, a Just-in-Time approach simply doesn’t reflect the semiconductor cycle.

Sustainability opportunities

Of course, supply chain reliability has become even more precarious recently. During the pandemic, even Apple had to reduce the production of iPhones by ten million units due to material constraints. From an industry standpoint, the fact remains that improving how the final product is produced will make a drastic impact upon overall sustainability.

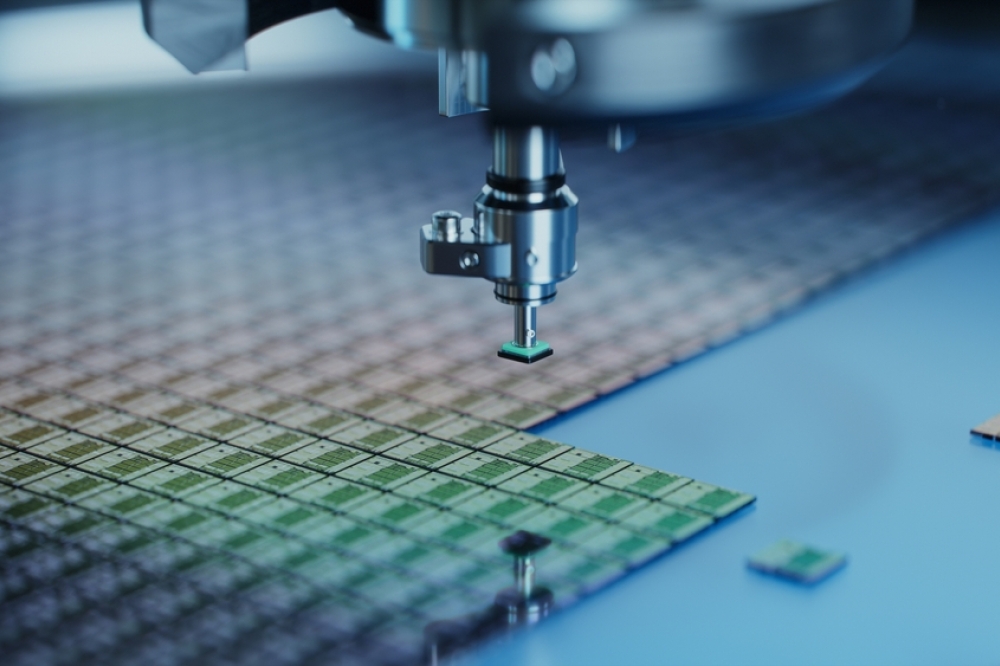

According to research from Accenture, the production of devices with attention to reuse, repair, resale, refurbishment, and remanufacturing can increase operating profits of manufacturers by 16%, while reducing material losses by 80%, and emissions by 45%.

Device engineers are increasingly expected to produce more sustainable designs, preventing the accumulation of electronic waste and late-stage recycling as a result.

But what about the rest of the value chain – beyond the fab, when chips are functioning within end-products?

Be smart to be sustainable

Forward-thinking semiconductor design can make chips a net contributor to sustainability by reducing the strain their production places on the environment. Combined with optimised processes within fabs, this represents a broader approach, increasing sustainability both in chip production and their subsequent deployment.

Embedding greater levels of intelligence with devices offers a real opportunity to take advantage of the ‘Artificial Intelligence of Things’ (AIoT): the ability of devices to process data on the edge, and then turn that data into action. From an environmental perspective, devices will be able to deliver new functionalities that offer power- and emission-saving qualities not yet seen in everyday devices.

For example, if a smart speaker consumes 4W for the entire time they’re on standby for a command, a more intelligent device could employ imaging AI to analyse the operating environment. This will enable it to determine whether there’s a human presence before listening for vocal inputs, which will cut power consumption by a factor of 10x for 75% of the typical day.

In future, manufacturers could develop gadgets with greater agency – for example, possessing the intelligence to purchase energy while automating domestic tasks. You can imagine a washing machine capable of trading for energy, dependent on the best spot price offered which, in turn, will reflect the impact on the environment.

Even in the short term, integrating AIoT functionality into existing household electronics could realise aspects of this far-reaching sophistication in 2023, if companies were so inclined. If achieved, the industry will be empowered to protect the environment to become a net benefit, as well as laying the foundations for future development through re-visiting the devices that are already at our disposal.