News Article

Direct Assembly Could Challenge CMOS Technology

Microchips are omnipresent in today's high-tech society and play primary roles in the inner workings of gadgets from your mobile phone to your coffee machine.

In the 1980s, CMOS, or complementary metal oxide semiconductor, made microchips economically feasible, says Sivasubramanian Somu, a research scientist in Northeastern's Centre for High-"‹"‹rate Nanomanufacturing. A critical element in any microchip is something called an inverter which is an electronic component that spits out zeros when you give it ones, and vice versa.

"A transistor (the basic element in an inverter), is a simple, extremely fast switch," Somu explains. "You can turn it on and off by electric signals." In the early days of computer technology, mechanical switches were used for computational operations. "You cannot achieve fast computations using mechanical switches," Somu points out.

So CMOS, which used electric signals to turn the switches on and off, represented significant progress in the field. But despite its relative cost savings, a CMOS fabrication plant still costs about $50 billion, according to Somu. "We needed an alternative, cost-"‹"‹effective solution that still can compete with CMOS at the foundry level," he says. CHN's proprietary "directed-"‹"‹assembly" approach could be that alternative solution.

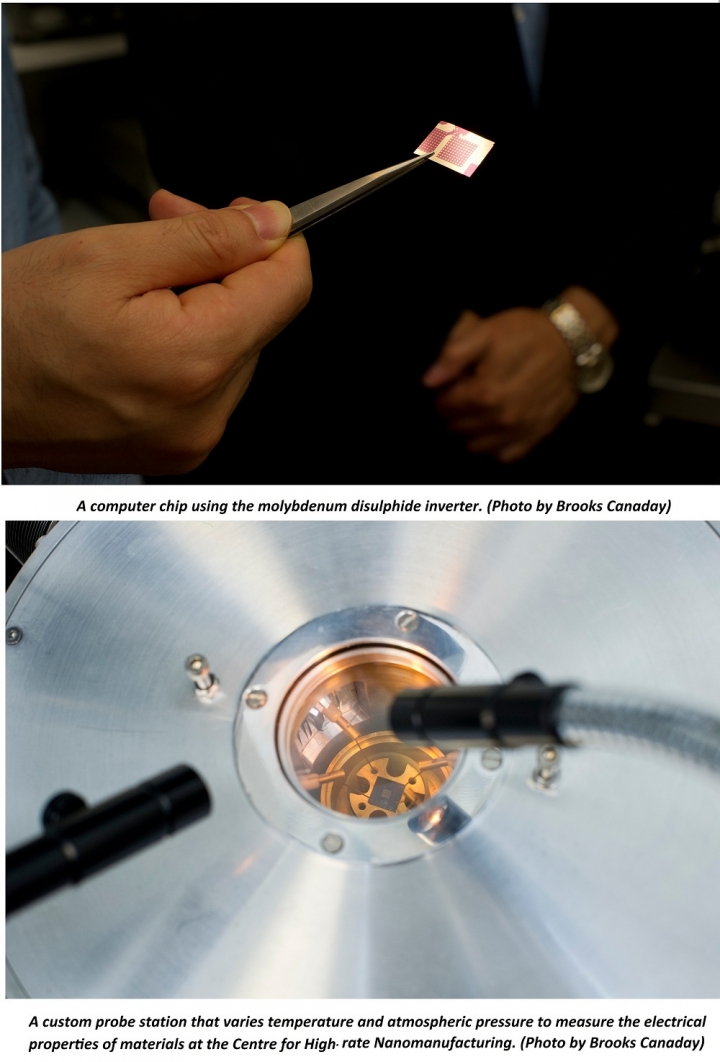

Instead of requiring several fabrication steps of adding and removing material, as in the case of CMOS, directed assembly is an additive-"‹"‹only process that can be done at room temperature and pressure. A fabrication facility based on this technology, Somu adds, could be built for as little as $25 million.

These cost savings would make nanotechnology accessible to millions of new innovators and entrepreneurs, and unleash a wave of creativity the same way the PC did for computing, says Ahmed Busnaina, the Director of the NSF Centre for High-"‹"‹rate Nanomanufacturing.

But creating a nanosized inverter is easier said than done, notes Jun Huang, a postdoctoral research scientist in the centre. Researchers have using materials like graphene and carbon nanotubes for creating inverters, but none of these has worked well on its own. Creating a nanosized inverter made up of different nanomaterials with excellent properties, Huang adds, could result in excellent complimentary transistors.

Using the directed-"‹"‹assembly process, the team created an effective complimentary inverter using molybdenum disulphide and carbon nanotubes. "At the nanolevel," says Huang, "molybdenum disulphide occurs in thin, nanometre-"‹"‹thick sheets." At this scale, he noted, the material begins to demonstrate transistor characteristics critical to the construction of a good inverter.

This result represents a step toward CHN's ultimate goal of enabling small and medium sized businesses to develop new, microchip-"‹"‹based technologies.