Overcoming Moore's Law With Carbon Nanotubes

A novel processing method will help pave the way for carbon technology as a viable alternative to silicon in future computing

IBM scientists have demonstrated a new approach to carbon nanotechnology that opens up the path for commercial fabrication of dramatically smaller, faster and more powerful computer chips.

For the first time, more than ten thousand working transistors made of nanosized tubes of carbon have been precisely placed and tested in a single chip using standard semiconductor processes.

IBM says these carbon devices are poised to replace and outperform silicon technology. They could allow further miniaturisation of computing components and advance future microelectronics.

Rapid innovation over four decades has enabled silicon microprocessor technology to continuously shrink in size and improve performance to drive the information technology revolution. Silicon transistors, tiny switches that carry information on a chip, have been made smaller year after year, but they are approaching a point of physical limitation.

Their increasingly small dimensions, now reaching the nanoscale, will prohibit any gains in performance due to the nature of silicon and Moore's law. Within a few more generations, classical scaling and shrinkage will no longer yield the sizable benefits of lower power, lower cost and higher speed processors that the industry has become accustomed to.

Carbon nanotubes represent a new class of semiconductor materials whose electrical properties are more attractive than silicon, particularly for building nanoscale transistor devices that are a few tens of atoms across.

For a start, electrons in carbon transistors find it easier to move in these structures as opposed to in silicon-based devices. And as such, they make it easier to speed up data transport.

The nanotubes are also ideally shaped for transistors on the atomic scale, another advantage over silicon. These qualities are among the reasons to replace the traditional silicon transistor with carbon "“ and coupled with new chip design architectures "“ will allow computing innovation on a miniature scale for the future.

The approach developed at IBM labs paves the way for circuit fabrication with large numbers of carbon nanotube transistors at predetermined substrate positions. The ability to isolate semiconducting nanotubes and place a high density of carbon devices on a wafer is crucial to assess their suitability for a technology. Eventually more than one billion transistors will be needed for future integration into commercial chips.

Until now, scientists have been able to place at most a few hundred carbon nanotube devices at a time, not nearly enough to address key issues for commercial applications.

"Carbon nanotubes, borne out of chemistry, have largely been laboratory curiosities as far as microelectronic applications are concerned. We are attempting the first steps towards a technology by fabricating carbon nanotube transistors within a conventional wafer fabrication infrastructure," says Supratik Guha, Director of Physical Sciences at IBM Research.

"The motivation to work on carbon nanotube transistors is that at extremely small nanoscale dimensions, they outperform transistors made from any other material. However, there are challenges to address such as ultra high purity of the carbon nanotubes and deliberate placement at the nanoscale. We have been making significant strides in both," adds Guha.

Originally studied for the physics that arises from their atomic dimensions and shapes, carbon nanotubes are being explored by scientists worldwide in applications that span integrated circuits, energy storage and conversion, biomedical sensing and DNA sequencing.

Carbon, a readily available basic element from which crystals as hard as diamonds and as soft as the "lead" in a pencil are made, has wide-ranging IT applications.

Carbon nanotubes are single atomic sheets of carbon rolled up into a tube. The carbon nanotube forms the core of a transistor device that will work in a fashion similar to the current silicon transistor, but will be better performing. They could be used to replace the transistors in chips that power our data-crunching servers, high performing computers and ultra fast smart phones.

Earlier this year, IBM researchers demonstrated carbon nanotube transistors can operate as excellent switches at molecular dimensions of less than ten nanometres "“ the equivalent to 10,000 times thinner than a strand of human hair and less than half the size of the leading silicon technology.

Comprehensive modelling of the electronic circuits suggests that about a five to ten times improvement in performance compared to silicon circuits is possible.

There are practical challenges for carbon nanotubes to become a commercial technology notably, as mentioned earlier, due to the purity and placement of the devices. Carbon nanotubes naturally come as a mix of metallic and semiconducting species and need to be placed perfectly on the wafer surface to make electronic circuits.

For device operation, only the semiconducting kind of tubes is useful which requires essentially complete removal of the metallic ones to prevent errors in circuits. Also, for large scale integration to happen, it is critical to be able to control the alignment and the location of carbon nanotube devices on a substrate.

To overcome these barriers, IBM researchers developed a novel method based on ion-exchange chemistry that allows precise and controlled placement of aligned carbon nanotubes on a substrate at a high density "“ two orders of magnitude greater than previous experiments, enabling the controlled placement of individual nanotubes with a density of about a billion per square centimetre.

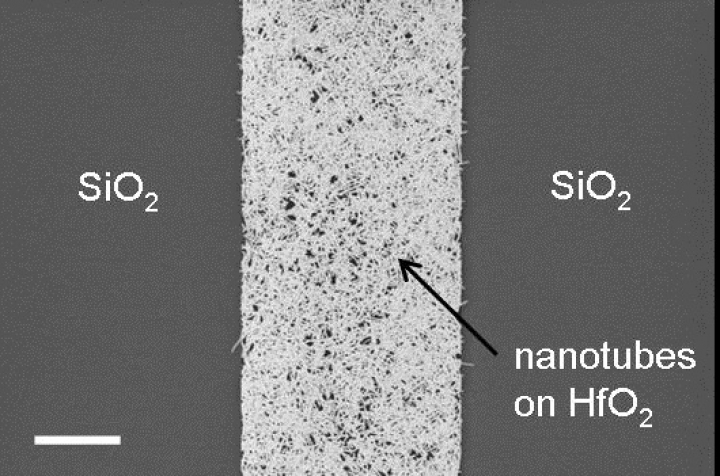

The process starts with carbon nanotubes mixed with a surfactant, a kind of soap that makes them soluble in water. A substrate is comprised of two oxides with trenches made of chemically-modified hafnium oxide (HfO2) and the rest of silicon oxide (SiO2). The substrate gets immersed in the carbon nanotube solution and the nanotubes attach via a chemical bond to the HfO2 regions while the rest of the surface remains clean.

By combining chemistry, processing and engineering expertise, IBM researchers are able to fabricate more than ten thousand transistors on a single chip.

What's more, rapid testing of thousands of devices is possible using high volume characterisation tools due to compatibility to standard commercial processes.

As this new placement technique can be readily implemented, involving common chemicals and existing semiconductor fabrication, it will allow the industry to work with carbon nanotubes at a greater scale and deliver further innovation for carbon electronics.