Microchips: EU off the pace in a global race

The target of 20 % global market share by 2030 appears out of reach. Member states and the private sector account for the lion’s share of investment; the European Commission manages much smaller funds. Issues like access to raw materials, energy costs, and geopolitical tensions pose additional challenges. Here we set out the findings and recommendations of the European Court of Auditors’ ‘The EU’s Strategy for Microchips’ Special Report.

It is very unlikely that the EU will meet its target of a 20 % share of the global market for microchips by 2030, according to a new report by the European Court of Auditors. While the 2022 EU Chips Act has brought new momentum to the European microchip sector, the investments driven by it are unlikely to significantly enhance the EU’s position in the field.

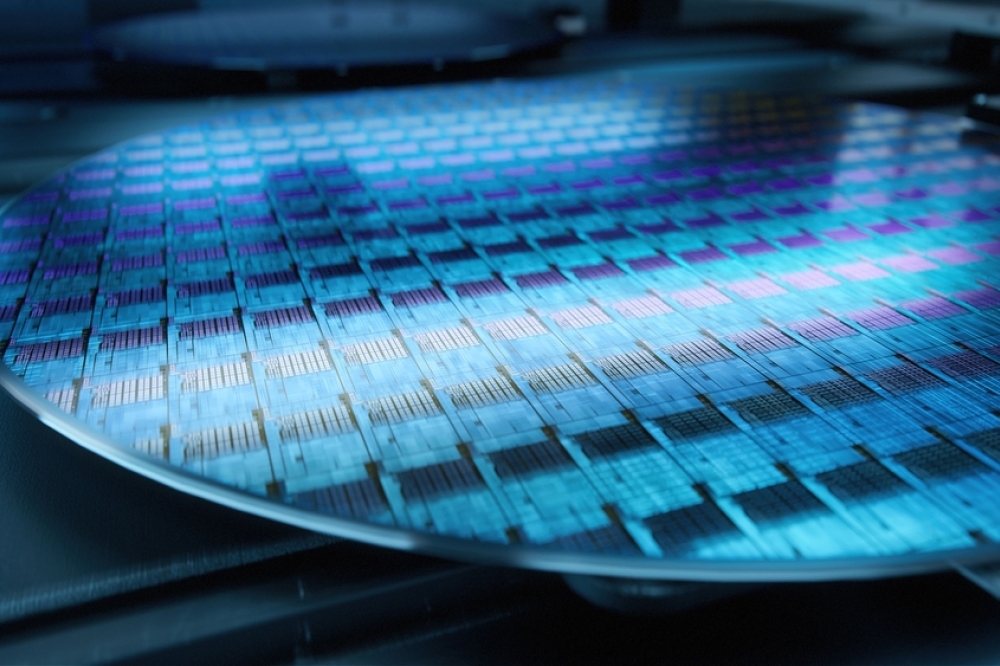

Microchips play a vital role in modern life, and the global shortage of microchips during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted their critical importance to the economy. The EU’s Digital Decade strategy set a target for the Union to gain a 20 % share of global production value in cutting-edge and sustainable microchips by 2030. The European Commission has made reasonable progress on implementing its strategy, but the auditors found that there is a gap to bridge between ambition and reality.

“The EU urgently needs a reality check in its strategy for the microchips sector”, said Annemie Turtelboom, the ECA Member in charge of the audit. “This is a fast-moving field, with intense geopolitical competition, and we are currently far off the pace needed to meet our ambitions. The 20 % target was essentially aspirational – meeting it would require us to approximately quadruple our production capacity by 2030, but we are nowhere close to that with our current rate of progress. Europe needs to compete – and the European Commission should reassess its long-term strategy to match the reality on the ground”.

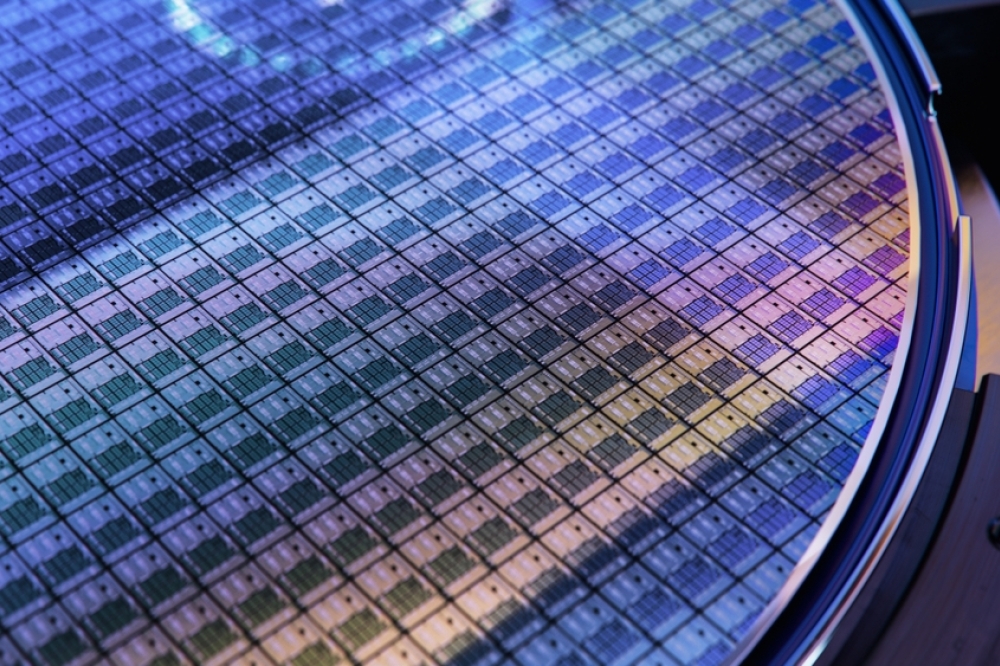

The Commission is responsible for only 5 % (€4.5 billion) of the €86 billion in estimated funding for the Chips Act up to 2030. The remainder is expected to come from member states and industry. For comparison, the top global manufacturers budgeted €405 billion in investment over just a three-year period, from 2020 to 2023, which dwarves the financial firepower of the Chips Act.

Nevertheless, as the auditors point out, the Commission has no mandate to coordinate national investments at EU level to ensure they align with the Act’s objectives. In addition, the Chips Act lacks clarity in its targets and monitoring, and it is difficult to know whether it takes proper account of the industry’s current levels of demand for mainstream microchips.

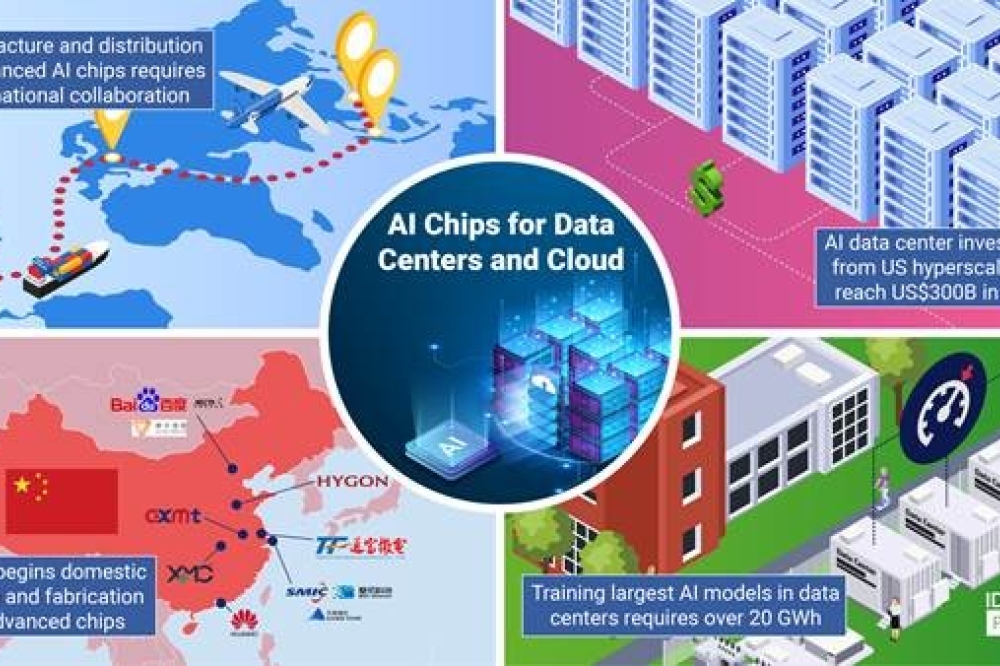

Several other key factors affect the EU’s competitiveness in the field, and the chances for successful implementation of the Chips Act. These include dependency on imports of raw materials, high energy costs, environmental concerns, geopolitical tensions and export controls, and a shortage of skilled workers.

Furthermore, the EU microchip industry consists of a few large enterprises focused on high-value projects, meaning that funding is concentrated. The cancellation, delay or failure of a single project can therefore have a significant impact on the whole sector.

Overall, the auditors found that the Chips Act is highly unlikely to significantly increase the EU’s share of the microchips market, or to meet the objective of 20 % of global output. Indeed, the European Commission’s own forecast, published in July 2024, predicts that despite a significant expected increase in manufacturing capacity, the EU’s overall share of the global value chain in a fast growing market would increase only slightly, from 9.8 % in 2022 to just 11.7 % by 2030.

The report in more detail

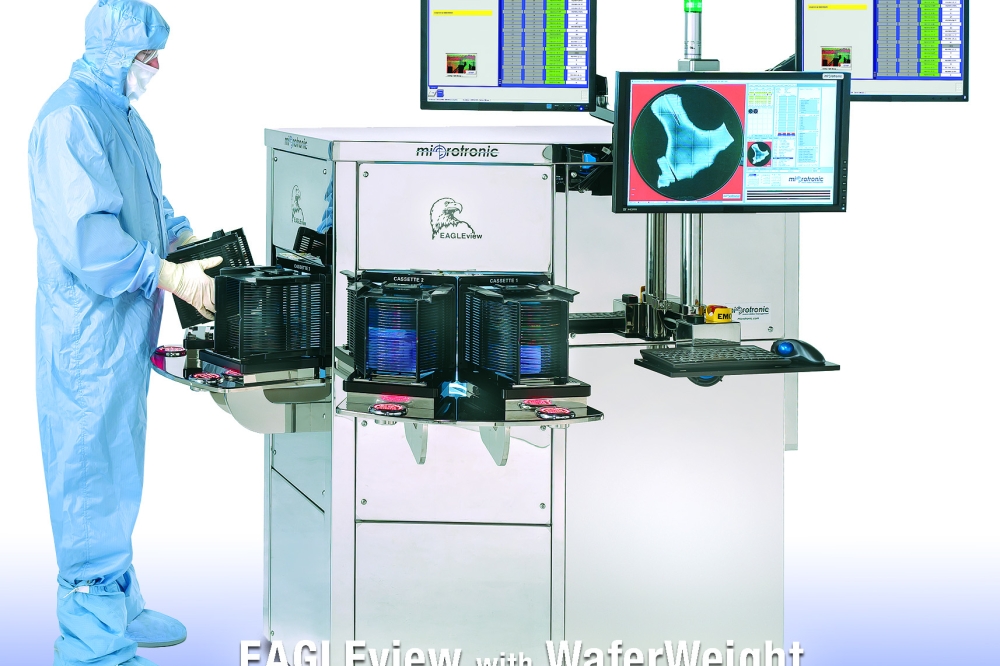

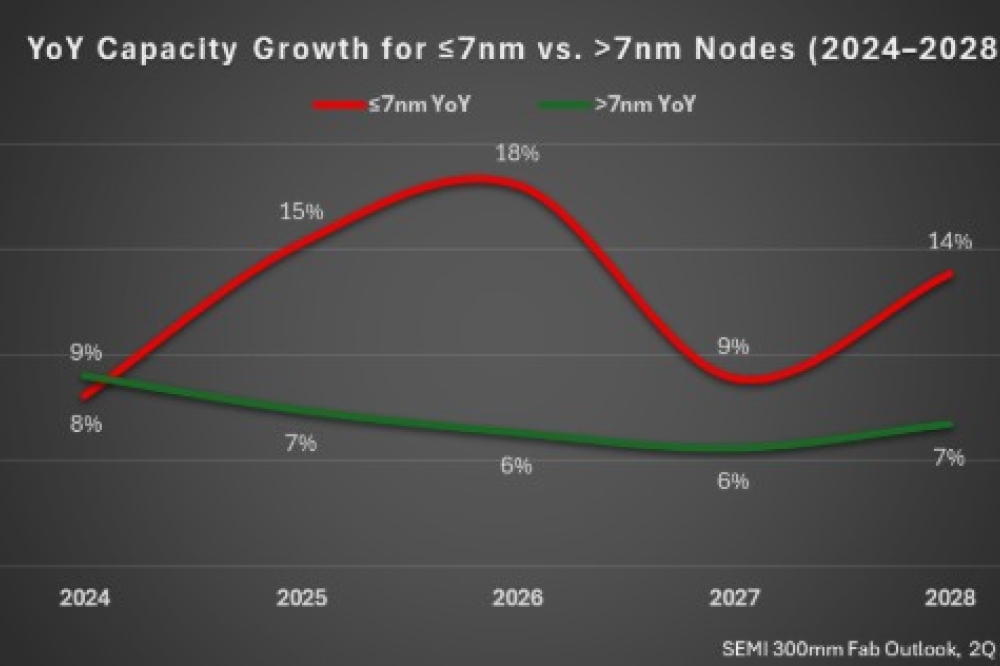

Over the years, the EU’s output of microchips has increased, but its share of global manufacturing capacity has decreased significantly. In 2020 the EU’s share was estimated at around 9 %1. In 2021, with the EU’s existing production sites operating at full capacity, the EU’s trade deficit for microchips was almost €20 billion2.

In the context of a very complex and globalised microchip value chain, total autonomy in microchip production is impossible.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted dependencies of the EU in the global microchip market, and the risk it represents for EU industry. For example, in the pandemic’s wake, the shortage of microchips for German carmakers caused car production to collapse to 1975 levels. This resulted in a recognition of the importance of security of supply (either manufactured within the EU or by reliable partners) in order to reduce dependency, and the need for an updated strategy on the EU’s role in the global microchip market.

As an element of the EU’s industrial policy, the EU Chips Act package3 (hereafter referred to as the Chips Act) was introduced in February 2022 to respond to the global supply chain disruptions provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic, which also affected Europe. The aim of the Chips Act was to confront microchip shortages and strengthen EU’s technological leadership. The Chips Act regulation entered into force in September 2023.

A range of public and private potential funding streams were identified for the microchip sector, with a minimum of €43 billion in policy-driven investments matched by a commensurate amount of private investment funding announced under the Chips Act.

The total can be estimated as at least €86 billion. Member states and industry stakeholders are expected to contribute substantial resources for the implementation of the Chips Act. The Commission adopted the EU’s Digital Decade target of 20 % by value of world production in cutting-edge and sustainable microchips by 2030, as the overarching objective of the Chips Act.

The objective of the audit was to examine how EU industrial policy supported strengthening the strategic autonomy of the EU microchip industry. We assessed the Chips Act’s design against the outcomes of the 2013 Strategy on the micro- and nano-electronic sectors, the alignment of funding with the EU’s strategic objectives, the timeliness and progress of the Chips Act implementation and reaching its overall objective, and other factors and risks affecting its success. This audit aims to contribute to crucial debates on the EU’s strategic autonomy and industrial policy, complementing the previous work as set out in the ECA’s special reports on circular economy, batteries, and hydrogen.

Findings and recommendations

Overall, we conclude that the Commission’s current strategy (the “Chips Act”) provided new impetus for action in the area. The Commission has already made reasonable progress in implementing its strategy, especially with regard to Pillar I, but we found weaknesses in its preparation, implementation and monitoring. Given the current level of investment in manufacturing capacity, the strategy is very unlikely to be sufficient to achieve by 2030 the very ambitious Digital Decade target of a 20 % EU share in the global market value chain by revenue. It is currently predicted that its share will be only 11.7 % by 2030. This target may also be considered overly ambitious for the Chips Act given the Commission’s limited mandate and resources and the success of the strategy being largely reliant on member states’ actions, investments of the private sector, and other crucial factors, such as the cost of energy.

The Chips Act package of 2022 was preceded by a 2013 Strategy that aimed to strengthen the micro- and nano-electronic sectors. While the EU’s microchip capacity increased substantially as of 2013, it did not keep pace with global growth meaning the EU’s share of the global market declined. The Chips Act picked up where the 2013 Strategy had left off, and responded to the microchip shortage crisis with a set of new actions. These included: reinforcement of technological and innovation capabilities and addressing gaps in the ecosystem (Pillar I); the principles to assess state aid support to investments in innovative “first-of-a-kind” (FOAK) production facilities (Pillar II); monitoring and response mechanisms to anticipate and react to crises (Pillar III).

However, the Chips Act was prepared in urgency, meaning the procedures usually applied when preparing legislation were not followed, such as evaluation of previous strategies, and an impact analysis of the proposal. Not fully analysing why the 2013 Strategy fell short of its goals and the resultant failure to draw lessons from the experience could mean that the Chips Act is susceptible to precisely the same problems. We found that the Chips Act lacks clarity regarding its targets and monitoring. In the absence of a full impact assessment, it is difficult to judge whether the Chips Act gives sufficient consideration to industry’s needs in mainstream microchips.

Investment decisions in the microchip industry are predominantly driven by private sector companies. In the context of the 2013 Strategy and subsequently the Chips Act, a range of different public and private potential funding streams were identified for the microchip sector. The Chips Act announced a total investment of at least €43 billion, with expected further private investment of a similar amount. However, the majority of these funds consist of the industry’s own resources or member state budgets, with the Commission being responsible for just a small part (approximately 10 % of public funding) of the total. The Commission has no mandate to coordinate national investments at EU level in order to align them with the Chips Act objectives. Overall, the Commission has only partial information on the total funding provided to, and used by, the industry, which reduces its ability to monitor progress and identify gaps and overlaps.

While we found that the projects receiving co-funding directly from the Commission, or via the Chips Joint Undertaking (JU) (and its predecessors the Electronic Components and Systems for European Leadership (ECSEL) and the Key Digital Technologies (KDT) joint undertakings), were generally well-aligned with the goals of the respective strategies, the arrangements in place to measure their effect were incomplete. The Commission also has incomplete information on the state aid investments’ contribution towards achieving the strategy’s objectives.

We found that the timeline for implementing the Chips Act’s three pillars is unclear, and their implementation is very unlikely to be sufficient to achieve the overarching objective. Pillar I is progressing well but suffering some delays. The uptake of FOAK investments under Pillar II is slow and unlikely to be sufficient for the overall digital target of 20 % to be met by 2030. Lastly, the coordination and crisis-monitoring mechanisms, which were expected to be available in the short term under Pillar III, are still in the very early stages.

Achievement of the Chips Act objectives does not depend solely on EU action, but is also determined by the level of private sector investment, the EU business competitiveness compared with competing global regions, and other crucial factors. The funding associated with the Chips Act may not be sufficient to support and stimulate the investment the industry needs to increase the EU’s share, and so meet the objective of 20 % of global output. Indeed, the Commission’s own forecast published in July 2024 predicts a slightly increasing market share to only 11.7 %. We also note that the industry is characterised by a relatively small number of large enterprises undertaking high value projects, meaning that funding is similarly concentrated. As such, the cancellation, delay or failure of an individual project can have a significant overall impact.

Finally, as the semiconductor industry is global, the EU faces intense international competition, as well as other challenges. Countries around the world have their own strategies for attracting investment, increasing their market share and strengthening the security of their supply. There are also other factors, which also depends on coordination between the EU and member states, impacting the EU’s competitiveness and the objectives of the Chips Act, such as export controls, access to the necessary raw materials, the cost of energy and environmental requirements.