Calls for more transatlantic research cooperation

Chips R&D is very expensive and it doesn’t make sense to duplicate capabilities. To get the full strategic value from their multi-billion incentive schemes, EU-US collaboration ‘is a must’ a joint Science|Business/CSIS conference hears.

The EU and the US have a rich history of collaborating on the development of semiconductors, but those links now need to be strengthened, according to speakers Tuesday at a joint conference on transatlantic semiconductor cooperation organised by Science|Business and a Washington-based think tank, the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

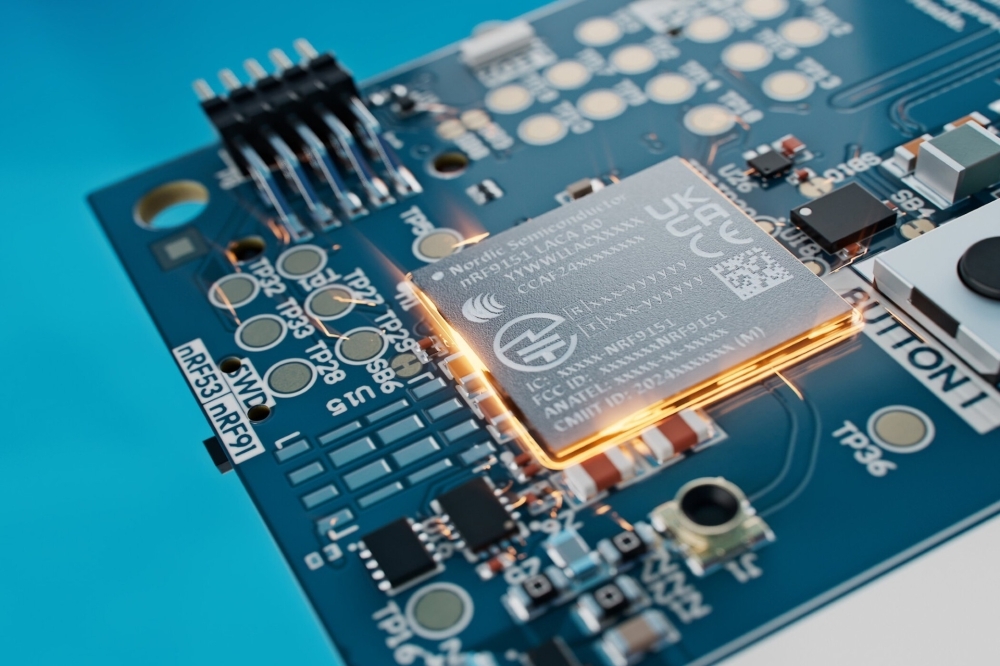

Both regions have made semiconductors a strategic priority, with the US $52.7 billion CHIPS & Science Act adopted in 2022, followed this year by the EU’s €43 billion Chips Act. But while both acknowledge the importance of international collaboration, few of the funds are earmarked for joint work with other countries.

Efforts to foster collaboration between the two legislations remain “too tepid”, said Alessandro Curioni, vice president of IBM Europe and Africa. Cooperation is usually seen as “nice to have” whereas “it has to be a must.”

This is part of a broader necessity to “improve transatlantic trust” so that fears of leadership changes do not stand in the way of long-term collaboration, Curioni said.

Similarly, Riccardo Masucci, director of security and technology policy at Intel said, “We should think of these two regions as one big transatlantic ecosystem, which means that we continue growing the regional supply chains, but we keep in mind that we operate in a much broader space. The real challenge now could be for the EU and US, instead of opening their programmes to the other side of the Atlantic, to start thinking of some joint programmes where there are common funds.”

In the past two years the US has stepped up efforts to ensure its innovations do not facilitate China’s military advancement, notably introducing export controls on equipment and technology for advanced semiconductors.

Both the US and Europe recognise the importance of protecting intellectual property from theft and leakage. But this “shouldn’t impinge on the ability for likeminded countries to work together,” Masucci said.

It’s also important to recognise the global nature of chip companies when designing programmes and allocating funding. “The base of where your headquarters is should not define whether you are eligible,” said Arco Krijgsman, head of public-private partnerships at the Dutch semiconductor manufacturing equipment specialist ASML, which has operations in more than 60 locations worldwide. More important is “where the work is done and which local ecosystem they feed,” he said.

With the industry facing a skills gap that is growing as demand for semiconductors grows, another critical measure is allowing the movement of workers and researchers across borders. “Restrictions on migration, especially for the talents we all need, are going to hamper the progress in our industry,” said Krijgsman.

Convincing member states

Despite the appetite for joint research, to date there are few initiatives specifically targeted at stimulating international collaboration in either the EU or US programme.

Jari Kinaret, executive director of the Chips Joint Undertaking, which implements research and innovation programmes included in the Chips Act, said the requirement for member states to match EU funding is holding back international collaboration within the public-private partnership. “It may be difficult to convince them to put their domestic research funding to organisations they don’t regard as domestic,” he said.

The joint undertaking is launching a small call with South Korea, but nothing as yet with the US.

Kinaret pointed to the US-EU Trade and Technology Council as the forum that could be used to build better cooperation in semiconductors. “[The forum is] creating politics, we are only implementing politics,” he said.

Companies that aren’t performing R&D inside countries belonging to the Horizon Europe research programme are not included in the initiatives launched by the EU Chips Act, such as pilot production lines and the cloud-based design platform. They can apply for other calls within the joint venture, but are unlikely to receive EU funding.

Multinationals like Intel and IBM with facilities in Europe are eligible for EU funding.

The US semiconductor package has allocated $500 million over five years to the State Department for an International Technology Security and Innovation Fund to develop secure supply chains in partner countries.

The main elements of the legislation are $39 billion in manufacturing incentives and $13.2 billion for R&D and workforce development.

“We do take cooperation as a high value activity for engagement, and to align shared interests, but it’s not as explicit inside the legislation itself,” said Eric Lin, deputy research and development director at the CHIPS office in the US Department of Commerce.

Many of the existing partnerships cited at the conference are not transatlantic. The US National Science Foundation oversees a collaboration involving 11 American and Japanese universities, called UPWARDS, which focuses on R&D and workforce development.

This week the Netherlands and South Korea agreed to cooperate on semiconductors, which will include a week-long training course in Eindhoven.

But while policymakers ponder how to stimulate US/EU collaboration, companies and research institutions have taken the initiative.

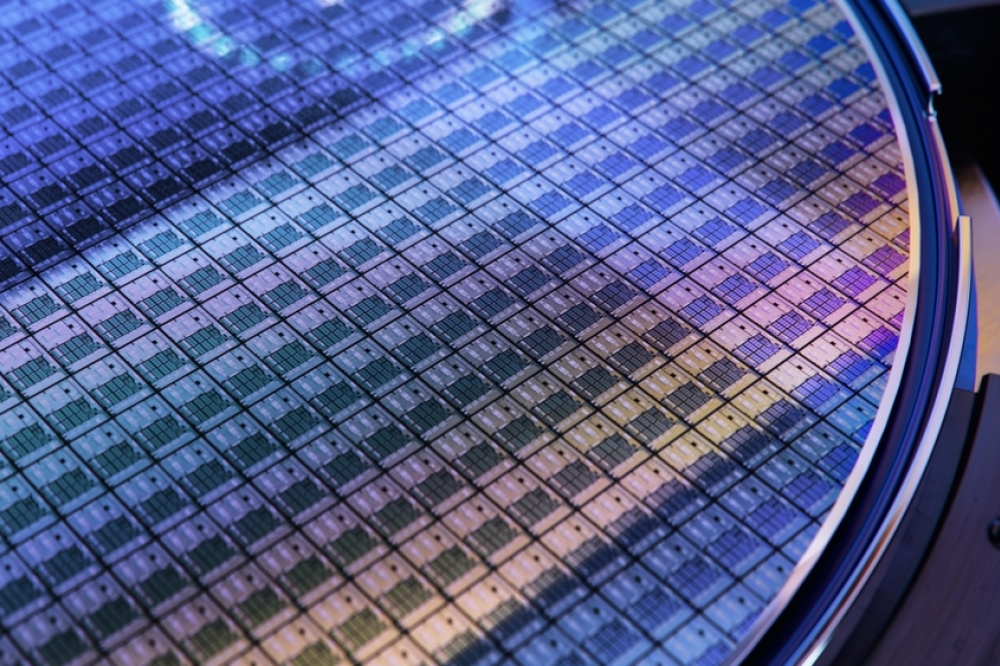

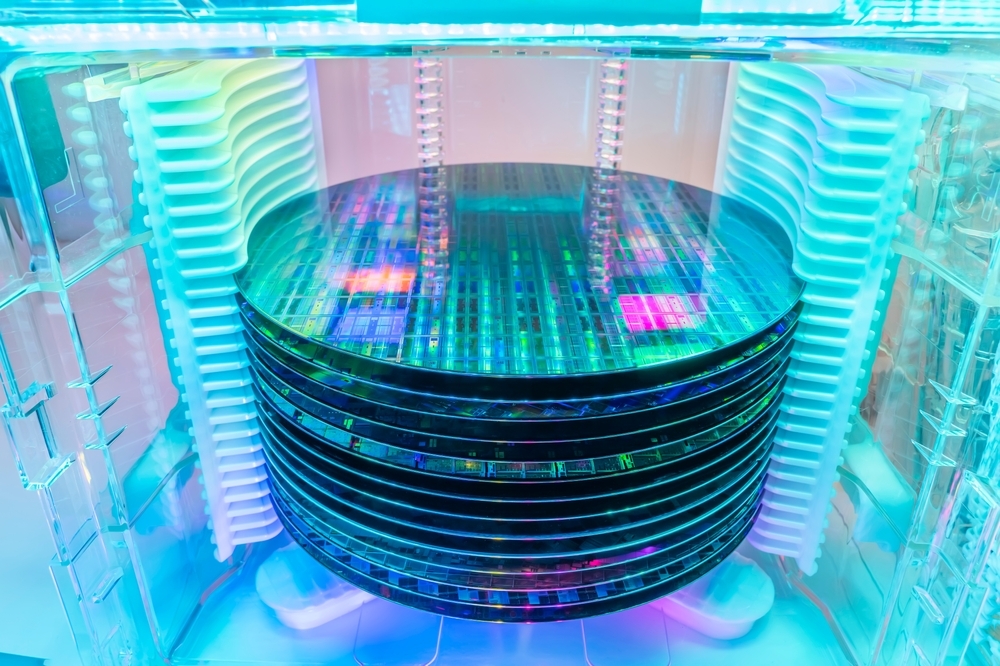

“We already have a solid base,” said Krijgsman. Extreme ultraviolet lithography technology, in which ASML is the world leader, started out as a collaboration between US and EU researchers.

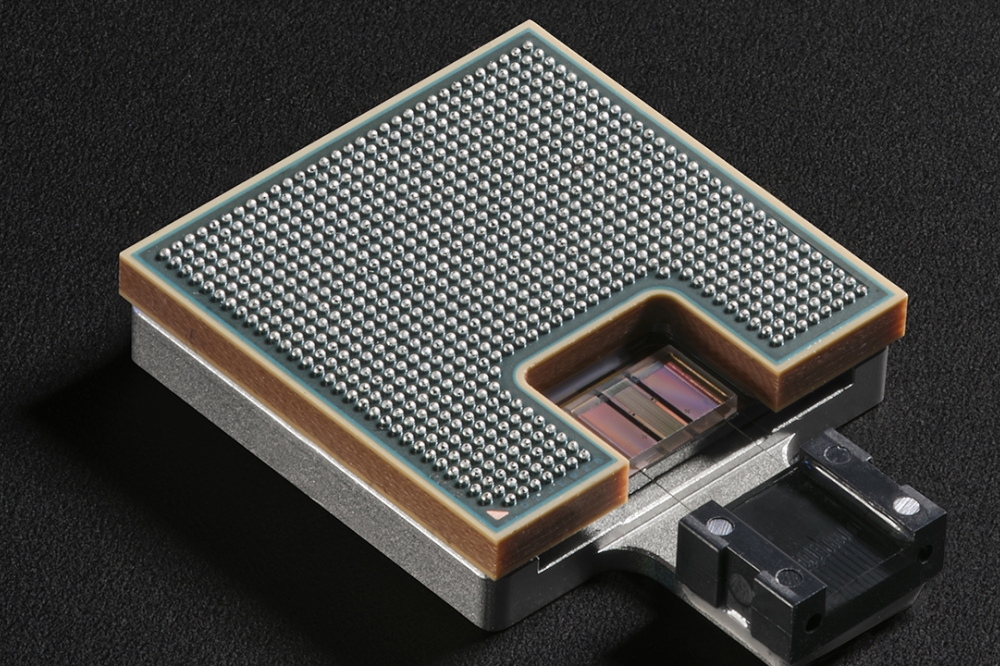

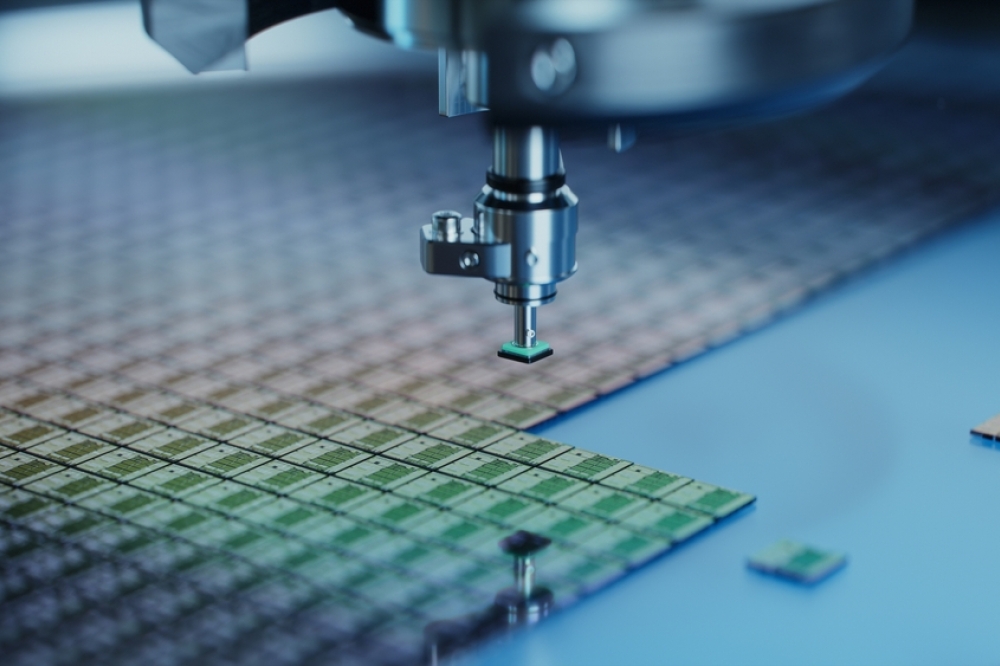

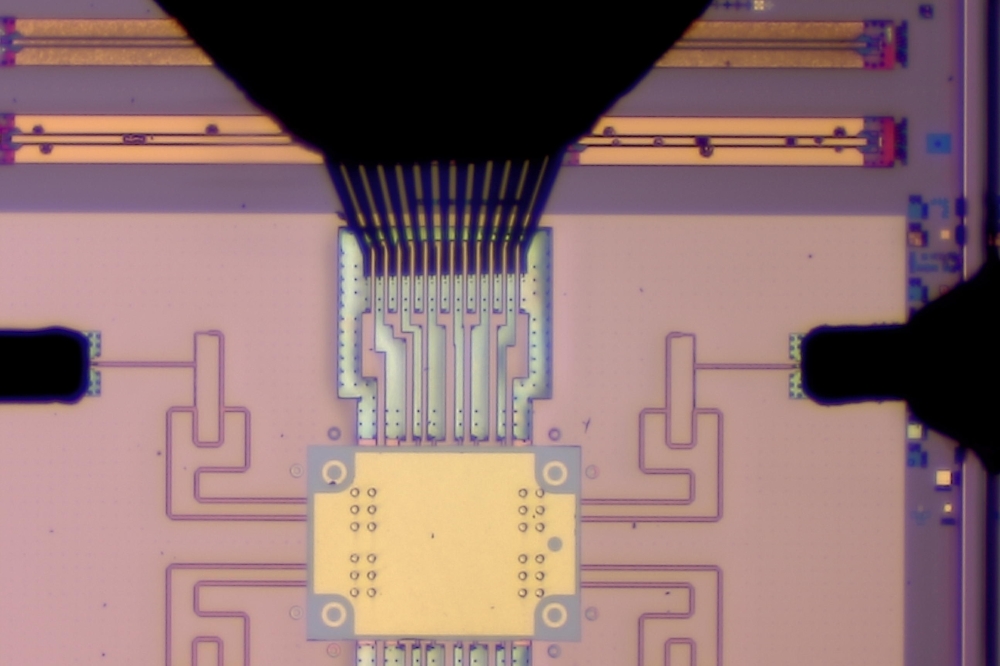

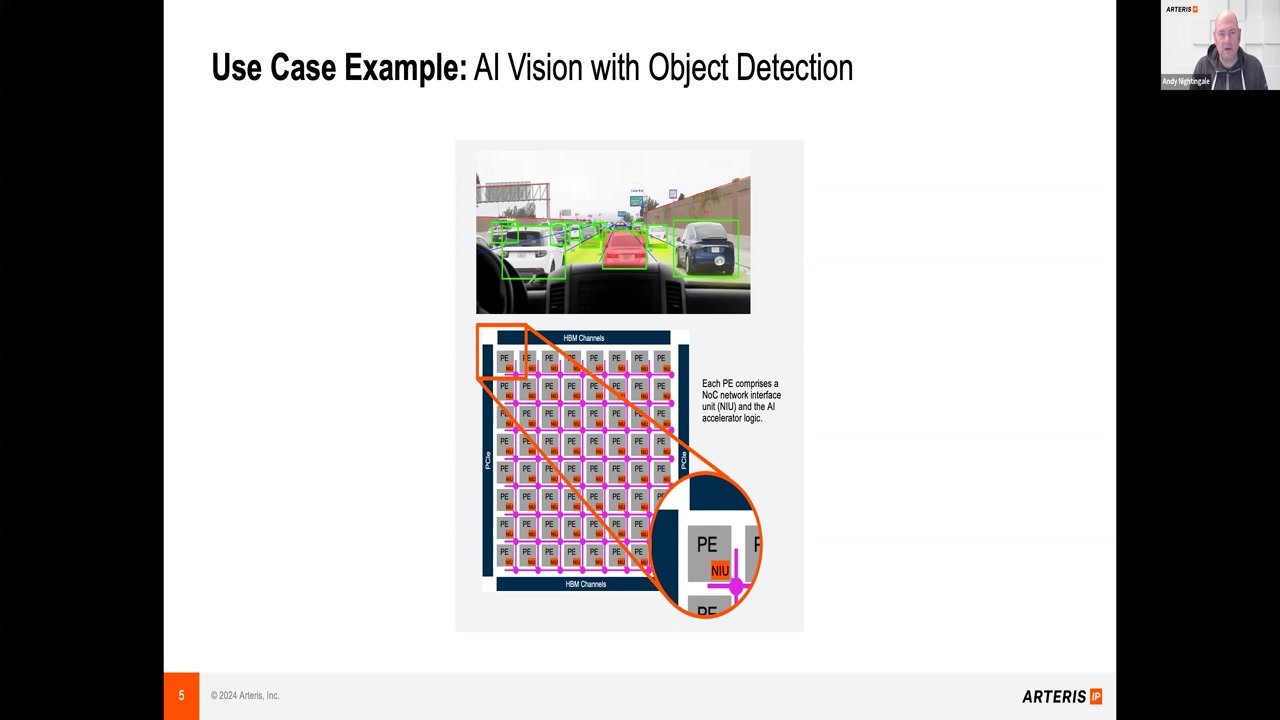

The NY CREATES Center for Research, Economic Advancement, Technology Engineering and Science, the recently announced a $10 billion investment in a new R&D centre at its Albany NanoTech Complex. This will be built around a “high numerical aperture” extreme ultraviolet lithography machine which will be delivered from ASML towards the end of 2025.

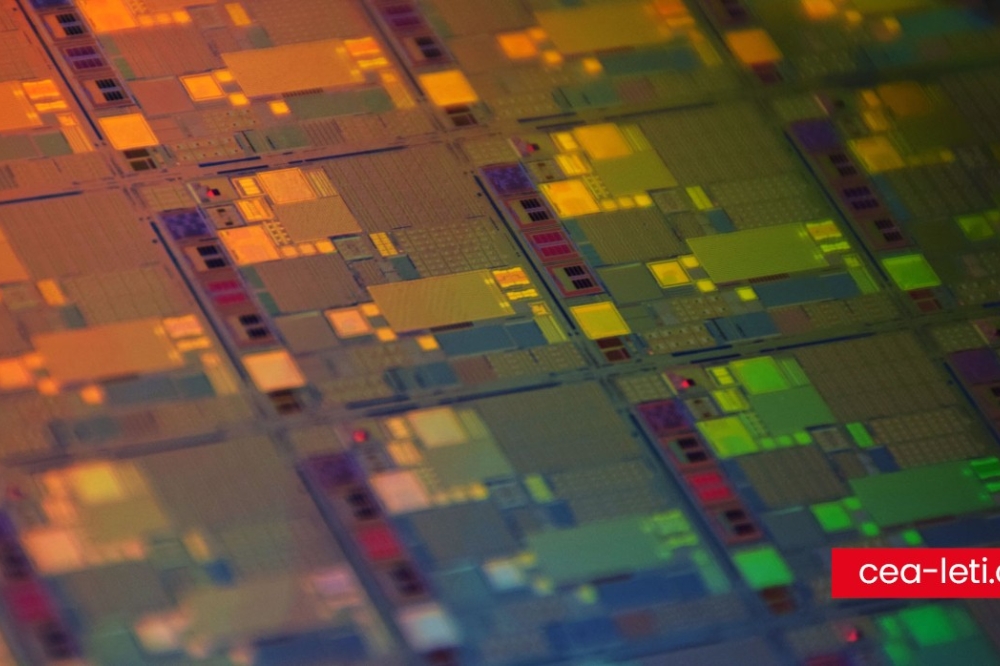

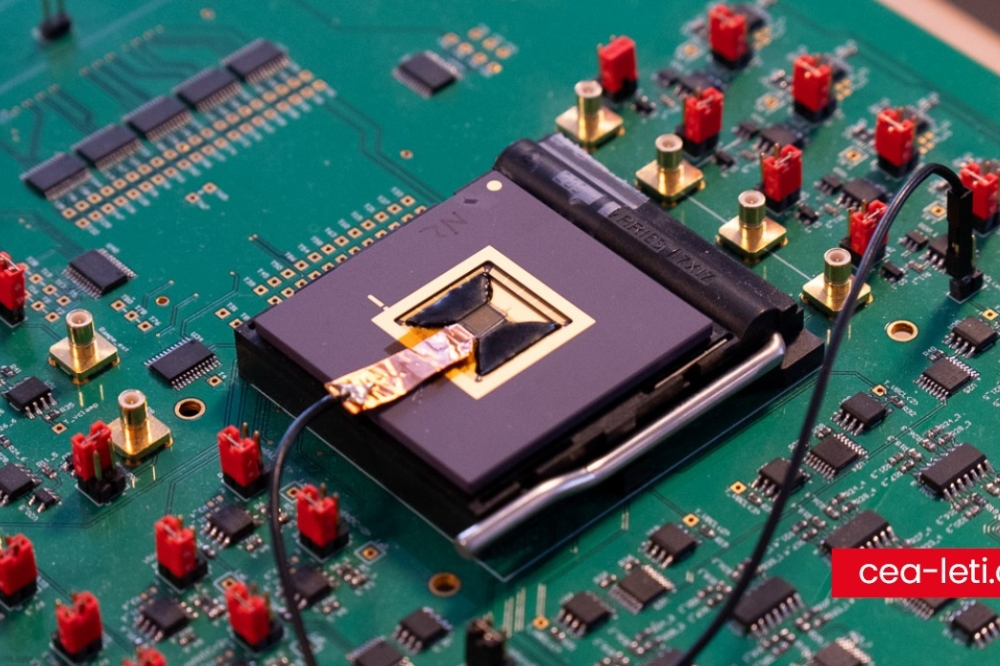

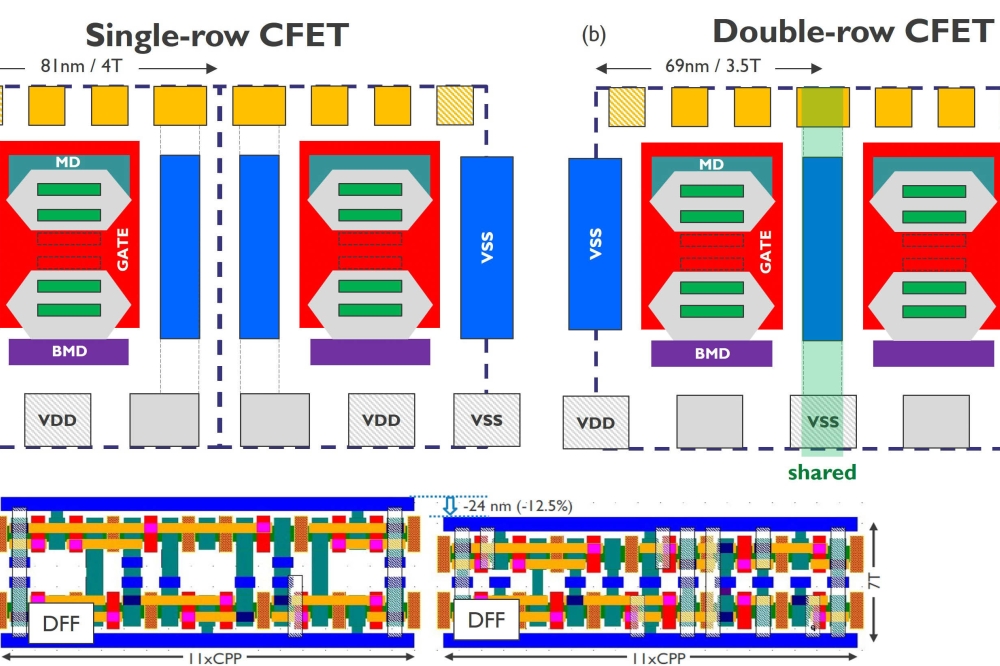

NY CREATES also works with partners including its counterpart, the IMEC research centre in Belgium. While the two play a similar role in the ecosystem, their respective focuses are complementary, said NY CREATES president David Anderson. “We can take some of the results of IMEC programmes, and put them into a full-flow manufacturing line and prove them to get them closer to manufacturing,” he said. “Research and development in semiconductors is very expensive, and it doesn’t make sense to duplicate capabilities around the globe.”

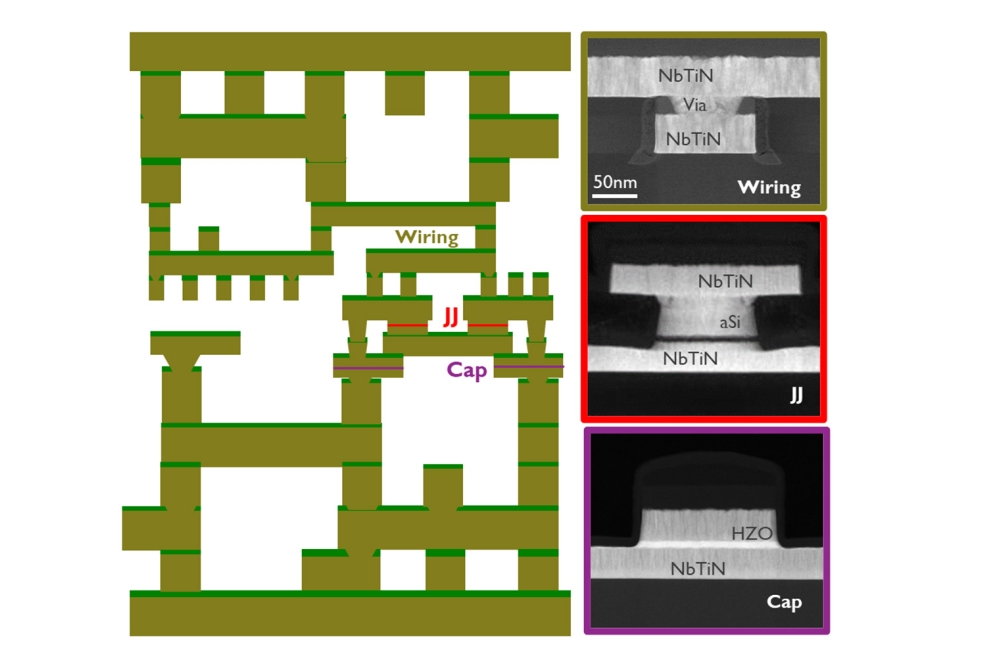

Gert Bergen, senior vice president of corporate development at IMEC, agreed the increasing complexity of chip technology requires even more collaboration. “We are on the right track” in terms of conversations happening at the EU-US Trade and Technology Council, between different government departments, and between companies and organisations, he said. “It’s imperative that when we move to implementation both on the European and the US side, and we start allocating budgets to specific roadmaps, that we contain this alignment, and we continue to drive this complementarity.”