Semiconductors in a world without PFAS

At the end of the day, the world’s reliance on semiconductors isn’t

going away, but semiconductor manufacturers likely won’t get to avoid

PFAS requirements, even if their products are vital. They almost

assuredly need to act now to avoid disruptions in their supply chain as

PFAS restrictions tighten.

BY NEIL SMITH, A REGULATORY AND SUSTAINABILITY EXPERT FOR ASSENT.

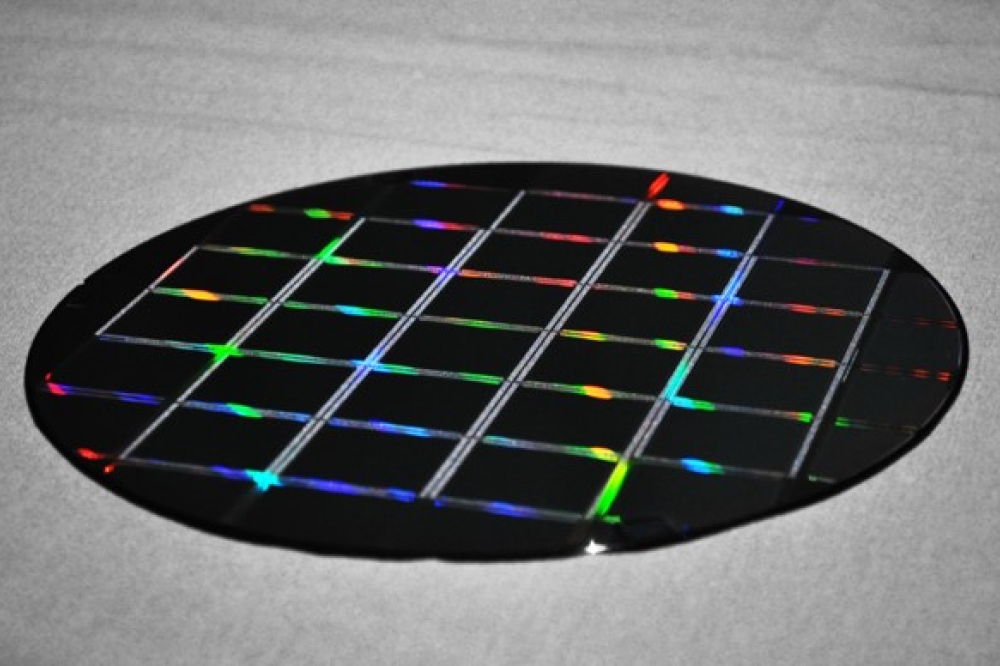

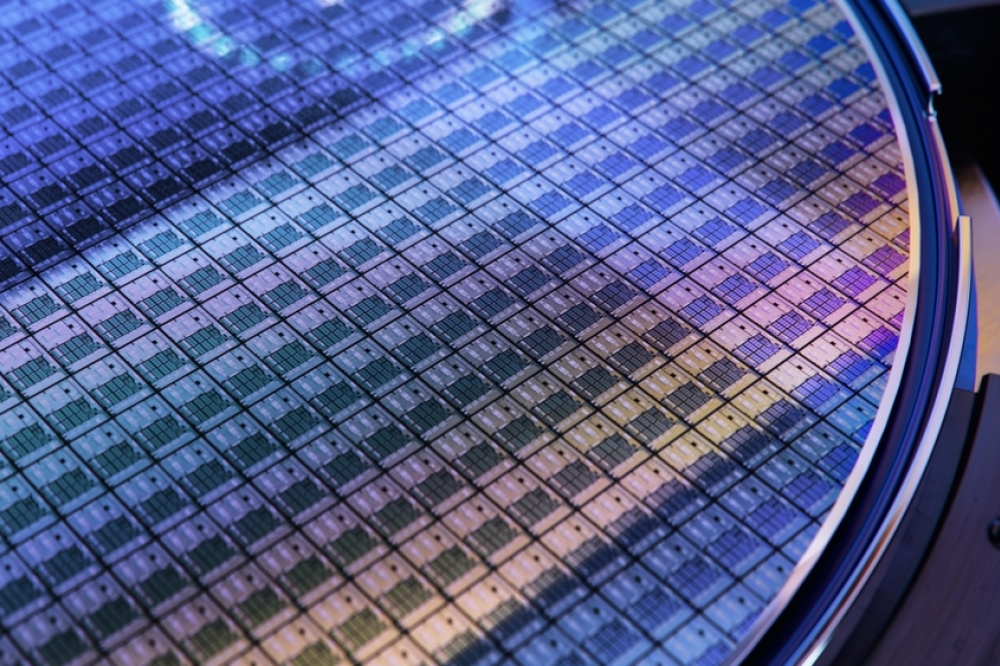

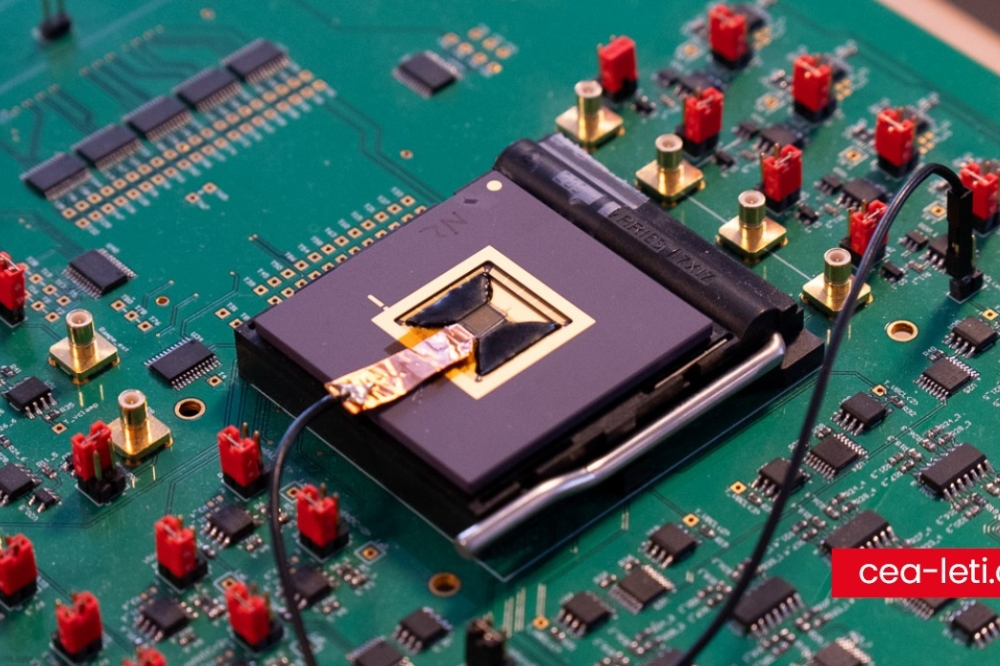

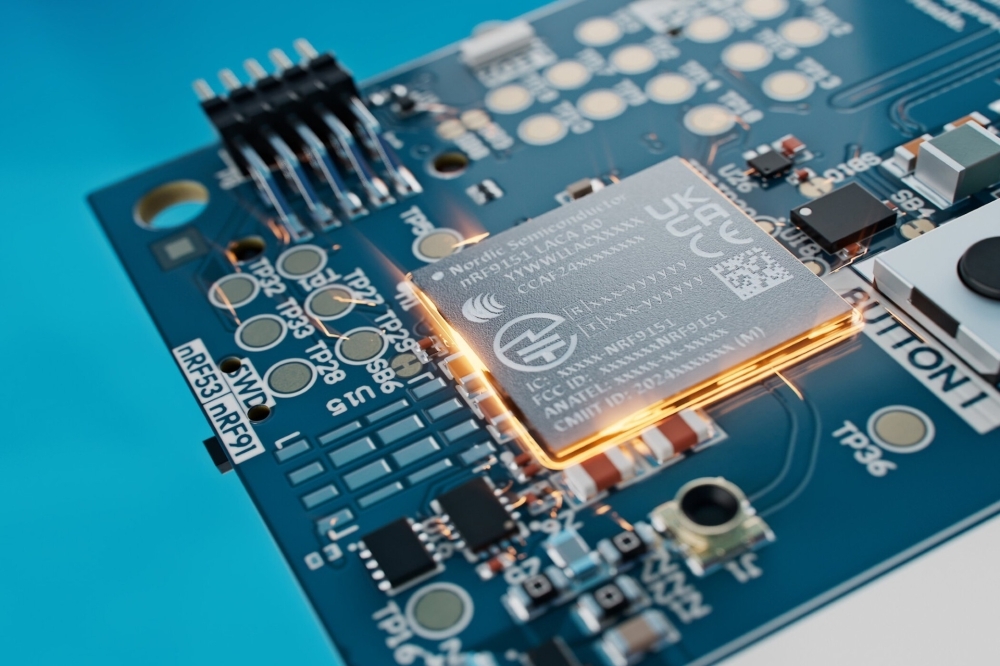

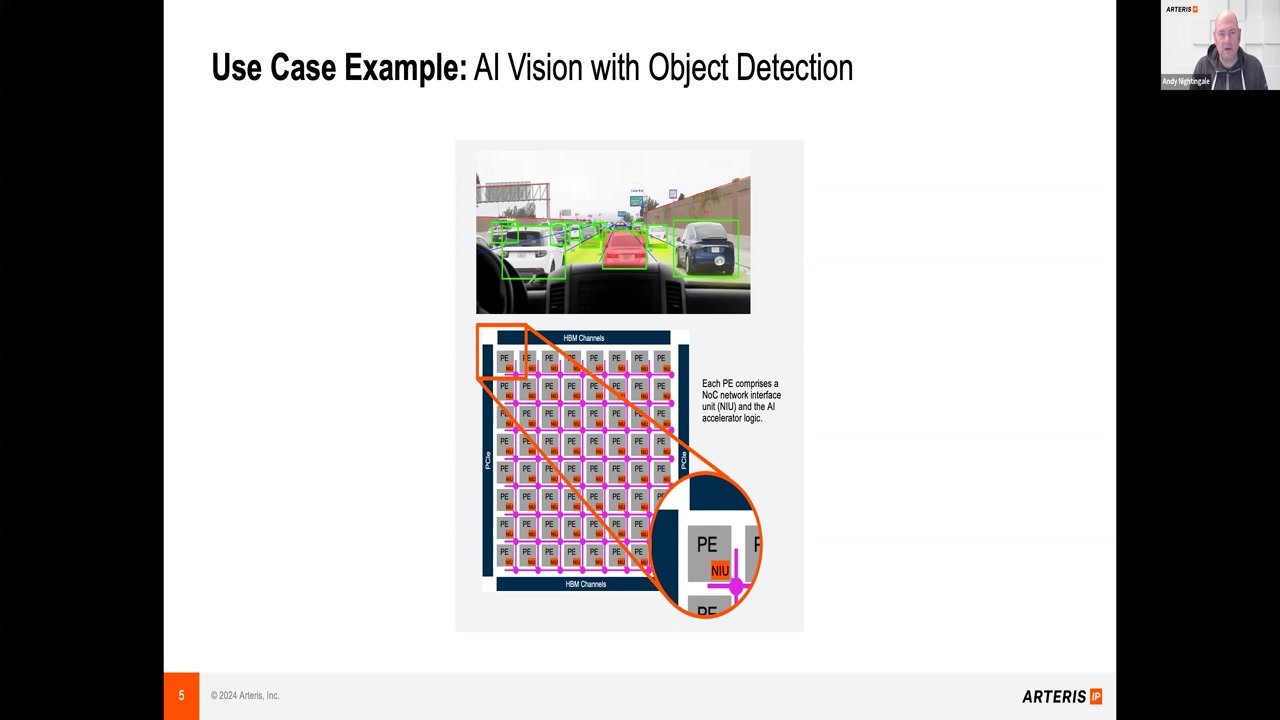

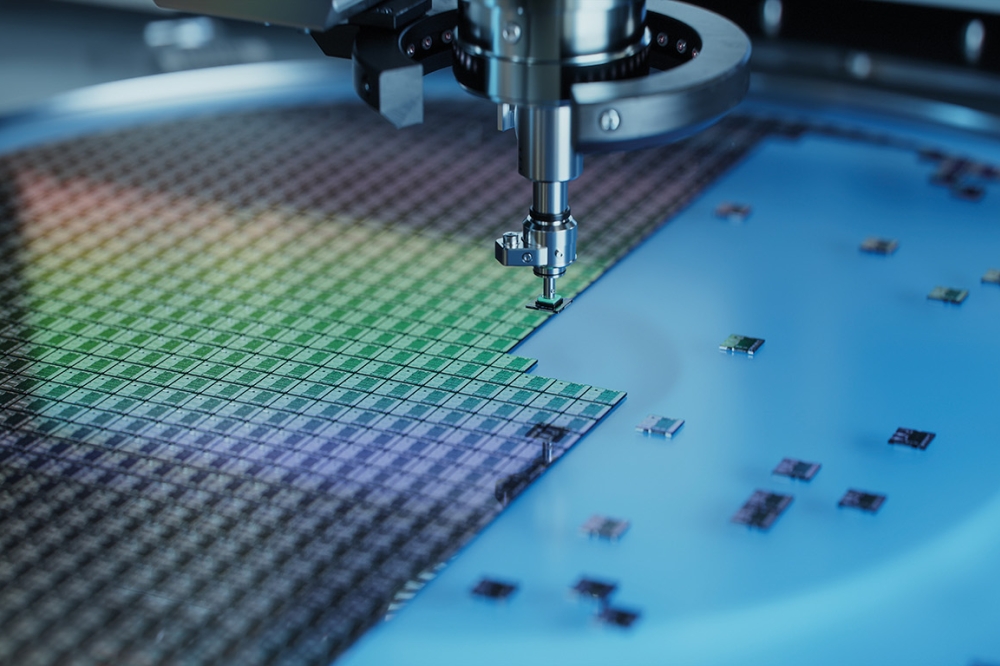

FROM THEIR USE in our smartphones and laptops, and video game systems and chips for our appliances and vehicles, semiconductors play a vital role in our economy and everyday lives. The increasing demand for semiconductors around the globe has a profound impact on both business and geopolitics, with manufacturers and governments positioning to protect their supply of these important materials.

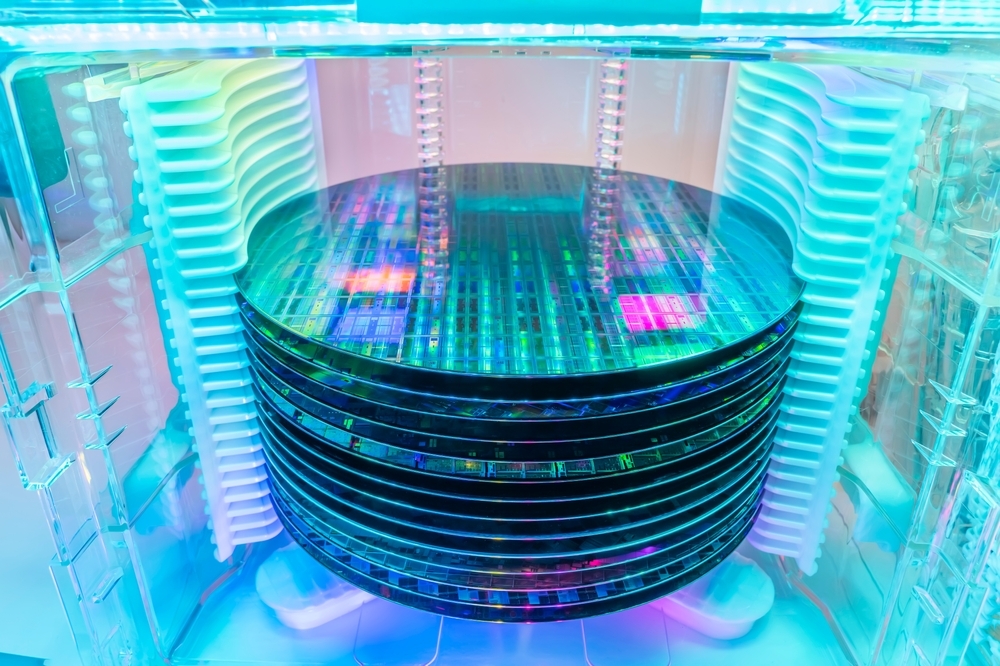

One complication to future semiconductor production is the current and upcoming changes to legislation surrounding the use of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), particularly in North America and the EU. These changes will result in restrictions on PFAS, potentially creating supply issues for companies in the semiconductor industry. Procurement professionals are working vigorously to ensure they have a sustainable stockpile of semiconductors to keep their operations running smoothly and avoid supply chain disruptions.

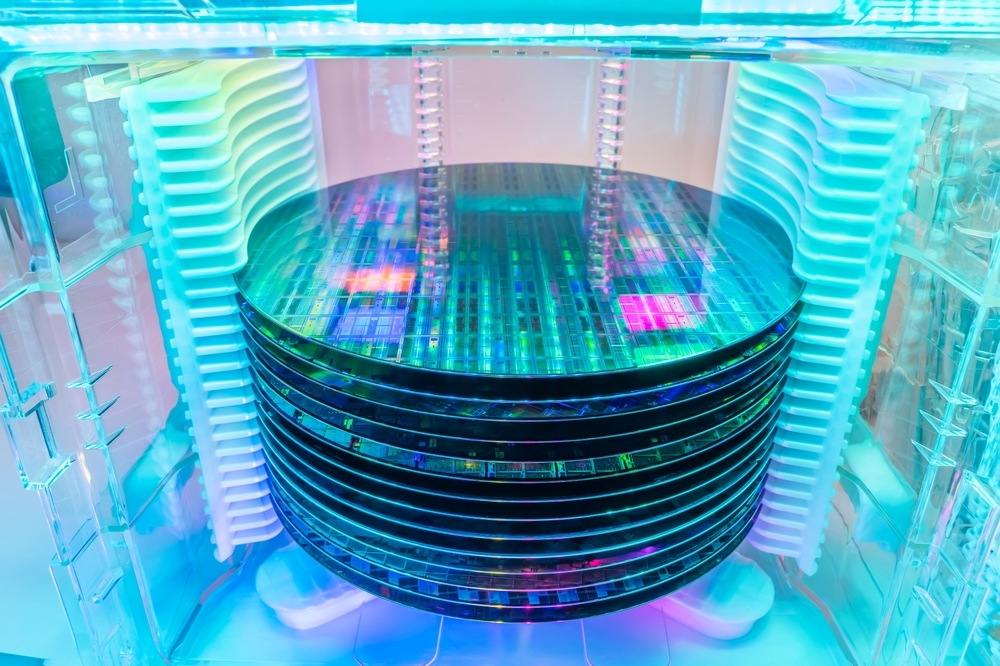

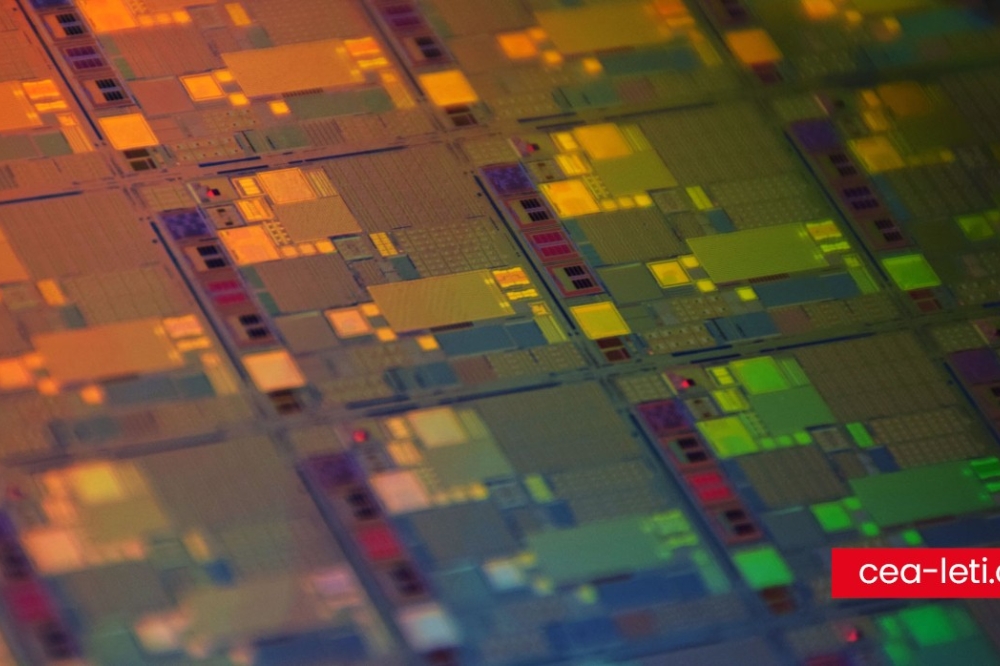

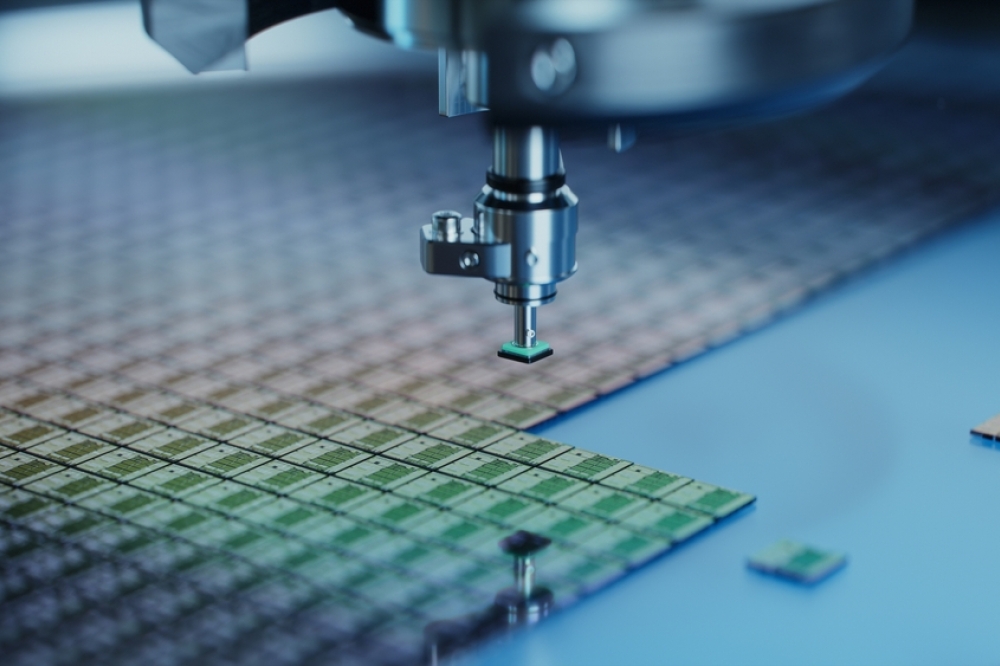

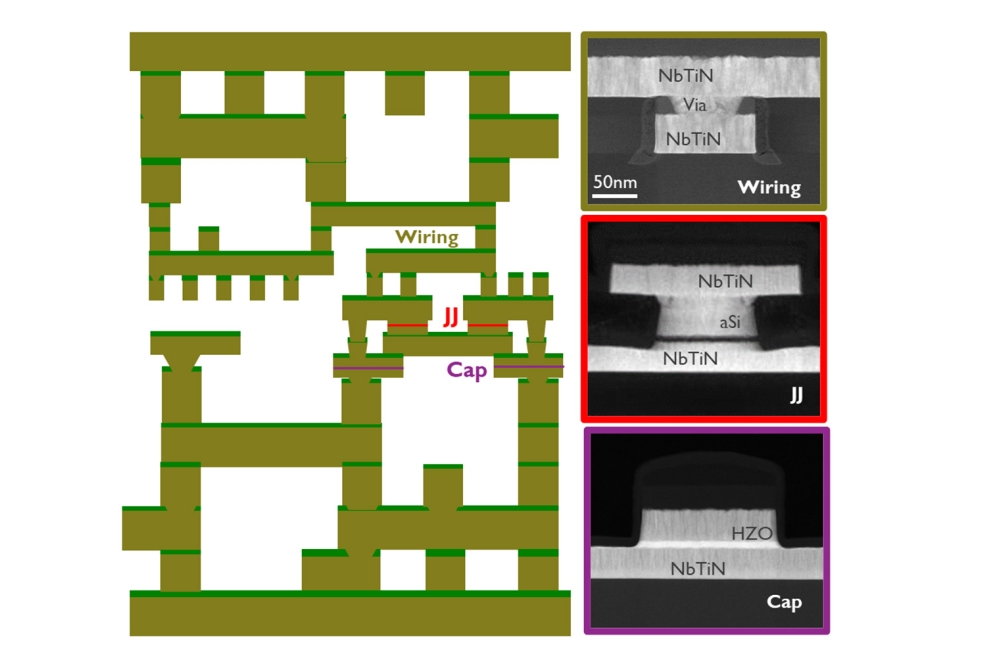

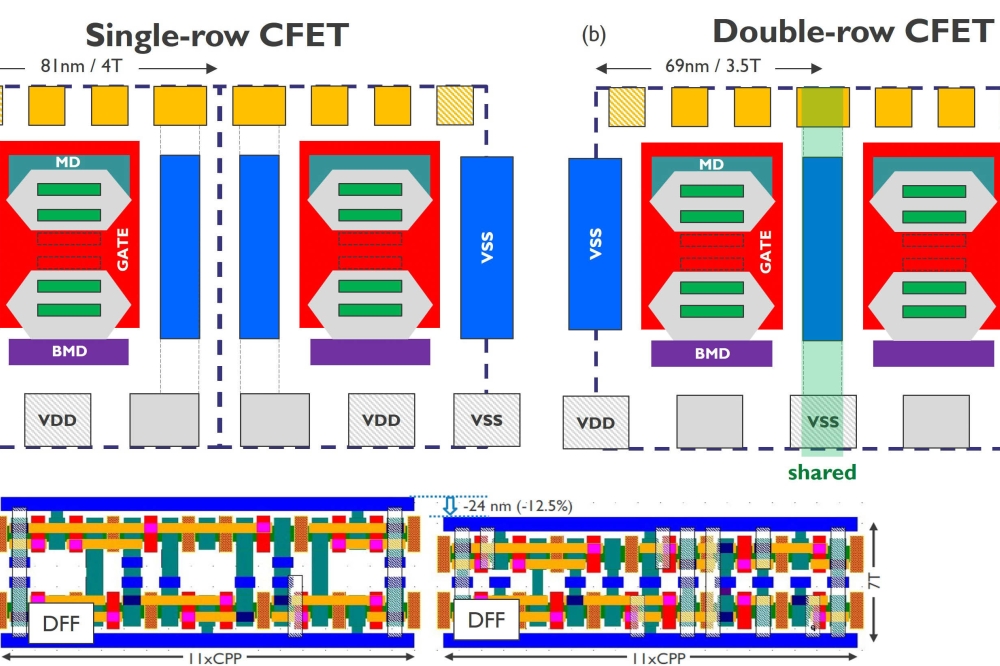

Why would the regulation of PFAS have such a profound impact on semiconductors? The equipment and technology used to manufacture semiconductors are often reliant on PFAS, and there are no suitable alternatives readily available in the marketplace. The reality is that as PFAS restrictions continue to tighten, they will create severe disruptions for manufacturers in the areas of intellectual property and confidentiality; machine obsolescence, redesign, and derogation/exemption determinations; equipment maintenance and repair; and management of end-of-life e-waste.

Confidentiality & intellectual property

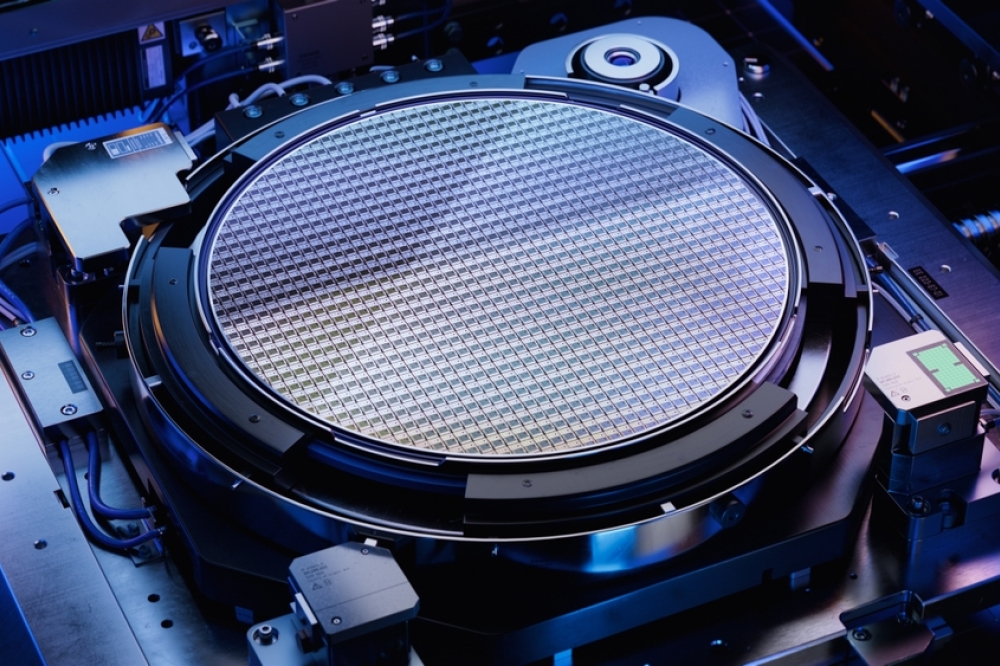

The importance of semiconductors is not lost on governments and NGOs. The EU’s REACH Annex XVII PFAS restriction proposal initially suggested exemption periods (derogations) of five and 12 years, based on risk and socioeconomic assessments. Semiconductor manufacturing was a commonly referenced example of why such a process was necessary.

Although the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) PFAS reporting rule does not currently exempt semiconductor manufacturers, state-level PFAS restrictions in Maine and Minnesota allow exemptions for unavoidable use.

Even in cases where exemptions exist, it’s not likely the derogation/exemption period will give industry enough time to adjust without significant pain and disruption. This is due to the sheer volume of data that needs to be collected from the supply chain concerning PFAS use, and the long lead time involved in product redesigns if they are necessary. To put it simply, if companies want to get ahead of their requirements, the time to map PFAS use in the semiconductor manufacturing process is now.

Even if an extended use period is granted, it doesn’t mean companies are exempt from submitting data on PFAS usage. Product-level reporting requirements have created new challenges for the semiconductor industry as well. Historically, downstream manufacturers that requested PFAS information from semiconductor manufacturers were denied on the basis that the data was confidential business information (CBI) or intellectual property (IP). Now, there is a growing understanding that these inquiries are based on regulatory pressures and reporting obligations associated with PFAS. This has resulted in a shift in the way these types of inquiries are handled. Companies that encounter true IP roadblocks may need to do joint filings with their suppliers, or the suppliers will need to work with customers so they can meet their obligations in a manner that protects supplier IP/CBI.

Machine obsolescence, redesign & derogation

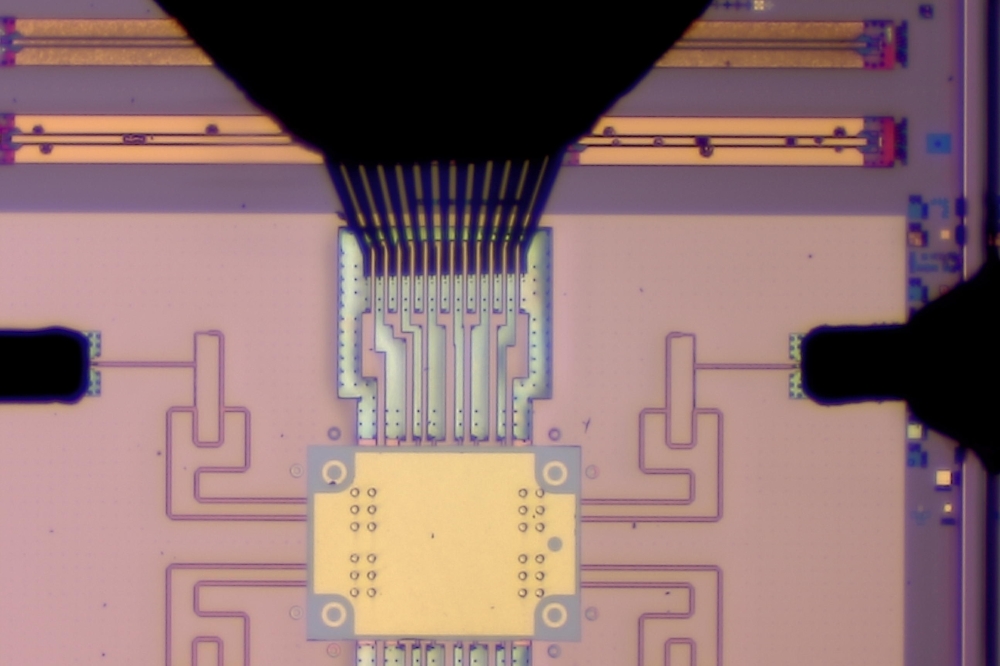

Staying ahead of upcoming regulatory changes also means taking a hard look at the semiconductor manufacturing equipment that relies on PFAS.

Even if a company receives a 12-year derogation, there is a strong possibility that these machines will have a decades-long service life that stretches beyond the regulatory obsolescence period. As such, the company may face significant challenges if they have to routinely re-supply parts or other materials that contain PFAS as part of maintenance and repair. The machine may become a victim of unplanned obsolescence much sooner than intended.

A derogation/exemption could allow for continued PFAS use for maintenance and repair of equipment already on the market. But there is still a risk that the manufacturers of maintenance repair and operations (MRO) parts and materials see the market dry up because they are now only supplying pre-existing machines — a small amount of the market. That, coupled with heightened regulatory scrutiny and increased liability burdens, could easily lead them to significantly raise prices or, in a worst-case scenario, exit the market completely. In that worst case, their customer would then have an unplanned, non-regulatory supply chain obsolescence. In many cases, this will be the reality more so than the regulatory obsolescence. Companies have so many different moving parts to consider in a world where PFAS is restricted. Even if they’re allowed to use those substances, will they still have access to them?

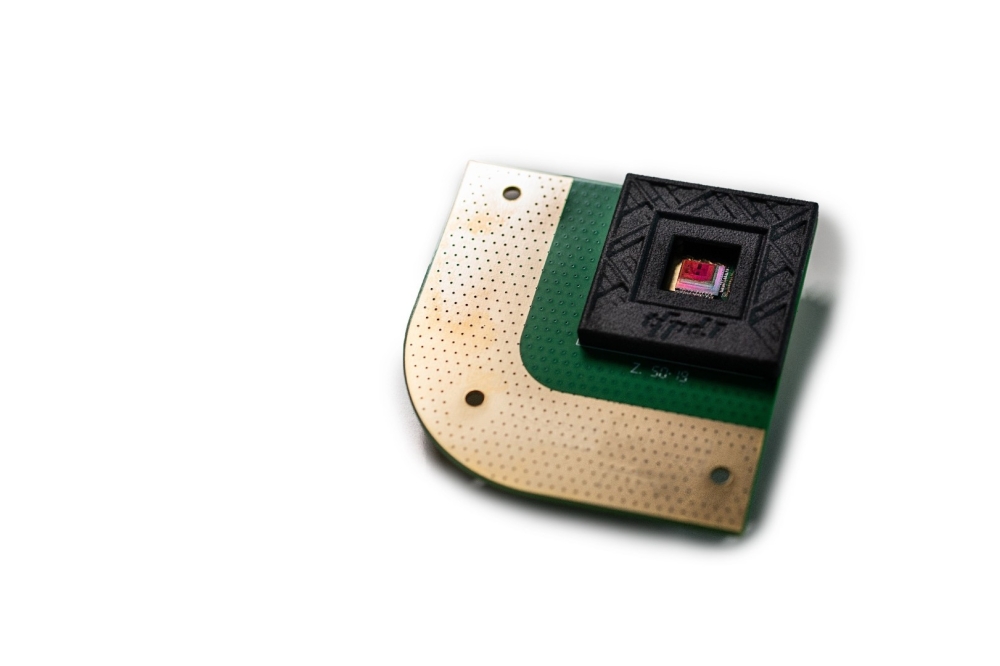

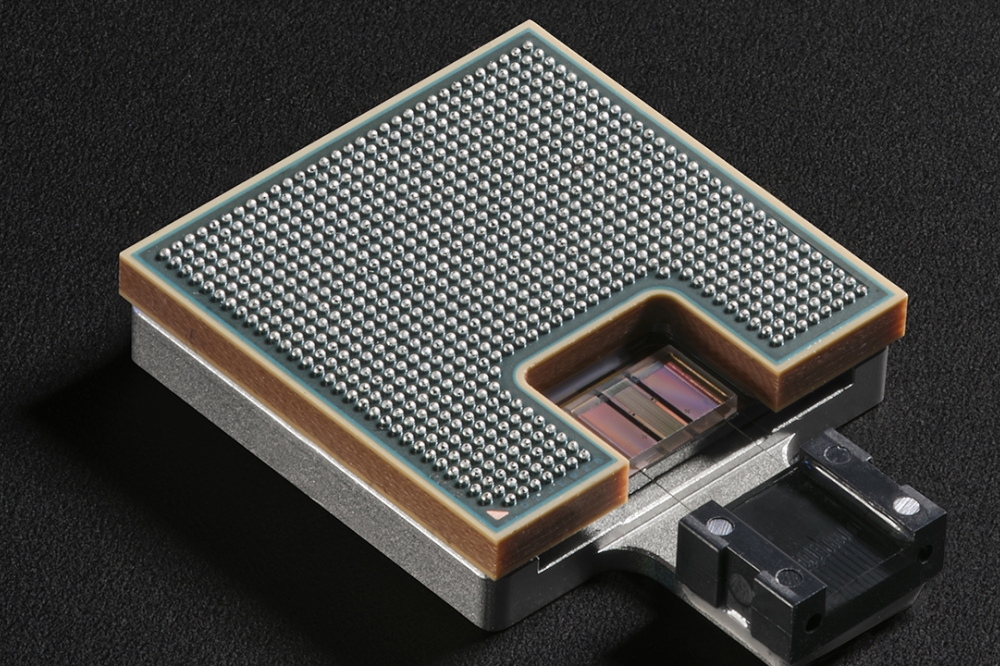

It is worth noting that the packaging side of semiconductor manufacturing could also be profoundly affected. Some of the semiconductor manufacturers use PFAS-containing protective coatings like films for shipping purposes, which would add another layer to their production challenges and potential supply chain disruptions.

End of life/e-waste

The EU is very committed to a green circular economy, including end of life. Many other jurisdictions globally also have e-waste extended producer responsibility programs in place. In the future, companies may have the challenge of figuring out a way to extract PFAS or “forever chemicals” from e-waste at end of life, which raises the question of how to treat and properly dispose of substances when there are no easy treatment technologies currently available. This derivative problem has to be solved, but it’s not even being considered as an overhang yet.

Manufacturing engineers will be asking, “How do I know where PFAS are in my products and manufacturing operations?”

Product engineers will ask, “How do I remove those PFAS and what do I do with them after?”

Everyone reading this is asking, “How did I find myself in this PFAS disaster?”

At the end of the day, the world’s reliance on semiconductors isn’t going away, but semiconductor manufacturers have a lot of hurdles to overcome in the transition to a PFAS-regulated and PFAS-restricted world. They will need to collaborate effectively with their customers and suppliers, and rely on deep visibility into their supply chains to keep their operations running smoothly.