Playing politics: The semiconductor supply chain

How should nations be looking to strengthen their semiconductor assets

instead? And what’s the purpose of barbed speeches, over-aggressive

competition, and international tariffs in a market that seems to depend

upon cooperation?

By Mark Lippett, CEO, XMOS.

It should be clear that no country – and even no continent – can be entirely self-sufficient. This is impossible.”

Thus spoke Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, when announcing the EU’s adoption of the European Chips Act in February 2022. The President was referring to the semiconductor supply chain: a complex concatenation of technologies and processes, from raw materials and extending all the way to fully produced chips with integrated IPs.

With each dependent upon others in the chain, and so many semiconductor niches to fill, placing meaningful investment in the supply chain is a huge challenge. Whereas manufacturers could once pour resources into producing chips for large, predictable, and pre-defined markets, like digital cameras, there are now so many diverse applications for chips that ‘general’ production is no longer realistic.

Consequentially, nations can’t simply throw money at the problem. Between the speed at which technology is advancing, the multi-year cycle required to produce semiconductors, and the shifting sands of trade restrictions and tariffs, total self-sufficiency on a national level is undeniably impossible.

So: why is this the case? How should nations be looking to strengthen their semiconductor assets instead? And what’s the purpose of barbed speeches, over-aggressive competition, and international tariffs in a market that seems to depend upon cooperation?

Half a world away

To paraphrase Chris Miller’s book, Chip War, a conventional computer chip could be based on blueprints designed by Californian and Israeli engineers and owned by the UK-based but Japanese-owned company, Arm. That device may be constructed in Taiwan, using specialised tools from one of five companies in the Netherlands, Japan, or back in California. After testing and packaging in South-East Asia, it’s finally shipped to China for assembly.

If any link in that chain fails, the process falls apart. No final device, and no sale.

One familiar example is the automotive industry, which incidentally triggered the global run on chips as it scrabbled for supply. You may remember brands like Alfa Romeo and Audi pausing UK production with almost-finished vehicles languishing on the production line during the pandemic. Markus Duesmann, Audi’s Chief Executive, specified an inability to address the “massive” shortage of computer chips” required to complete their manufacture.

In a conventional business environment, and especially one squeezed by the pandemic, a constrained supply would normally invite investment to plug the gap – just make more of what you need, right? But for a market as global, interconnected, and complex as the semiconductor supply chain, there is no financial panacea.

Money for nothing

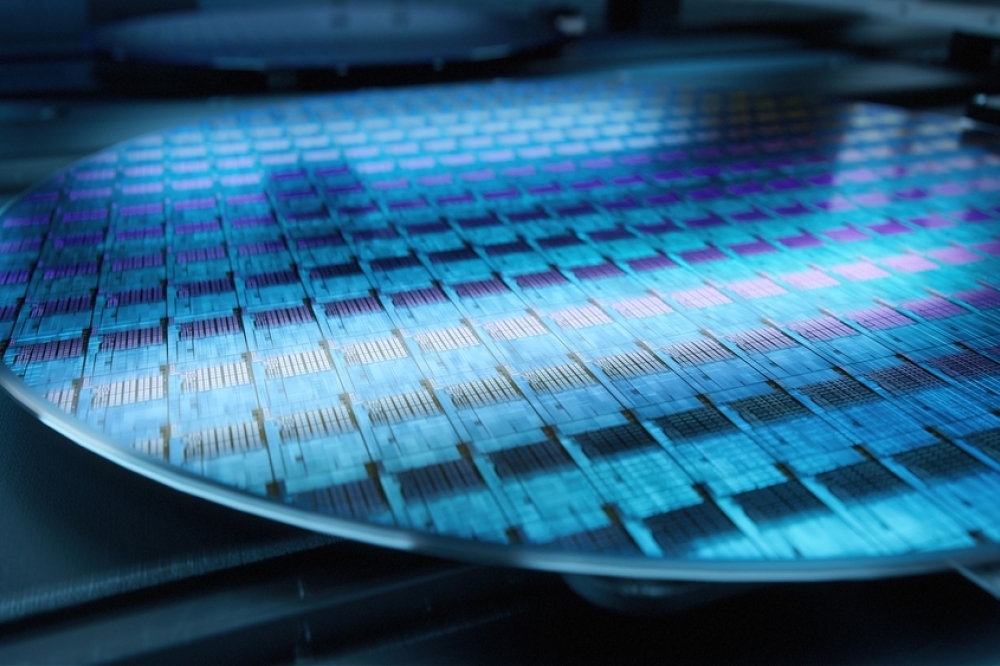

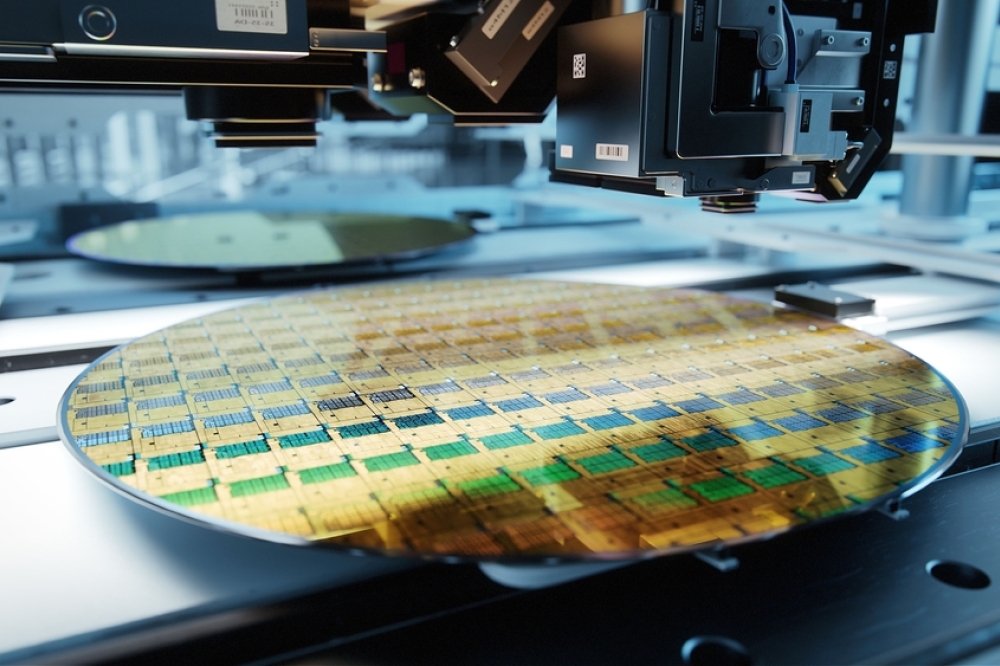

Between the time it takes to build a fab and then produce production silicon, the best part of a decade could have passed between identifying a problem and establishing a self-sufficient solution.

During that period, technology will continue to advance at blistering pace. TSMC has announced its intention to begin producing 3nm wafers in 2026, and has teased ‘key features’ of 1nm chips. But most technologies, and businesses, don’t rely upon these bleeding-edge technologies. So, if you spin up a new fab, it’s impossible to guarantee that your target audience is there on arrival. Will you be too early, too late, or otherwise redundant by the time the facility is operational?

Beyond that, the market is changing, too. The sparring between the US and China when it comes to securing their respective supply chains has seen tariffs applied to both sides, extra funding granted to domestic ventures, and smaller countries in between being pressured to pick sides. Market forces could make certain technologies or businesses redundant or surplus to requirements by the time they can be brought to bear.

It’s no surprise to see some of the biggest automobile brands in the world – BMW, Ford, Mercedes, Volkswagen, and more – continue to report frustrations eighteen months on from Alfa and Audi in the throes of COVID. Investment is being proffered, but timescales are long and the outcome may be a supply chain capacity that is overkill in some areas and absent in others. Von der Leyen’s announcement specifically states that the US’ $52bn CHIPS Act, and China’s reported $143bn investment in its domestic semiconductor industry, have similar goals despite the political bullishness – will the outcome of these investments cover all bases?

Trailblazing

So: if independence is impossible, why such heady investment?

If intercontinental outsourcing is necessary, we must have a seat at that global table – earning that seat by bringing something unique in terms of technology or IP that other nations need. While funding in the US and China is more about getting as close to self-sufficiency as possible, for smaller nations, the goal is to synonymise themselves with a small but pivotal link in the global semiconductor value chain.

The Netherlands is one such example. With the EU’s semiconductor capabilities distributed throughout the bloc, smaller nations tend to have specialisations rather than broad capabilities. The jewel in the crown of the Dutch is ASML, which has a worldwide monopoly upon the production of Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography (EUV) machines – without which the production of advanced chips is virtually impossible.

As a result, the small European country has been at the centre of a tug-of-war between China (which accounts for 15% of ASML’s annual revenue) and the US (which seeks to take advantage of that supply for itself.) It has modest natural resources and chip production capabilities, and yet it is universally acknowledged as a crucial element of semiconductor production.

This is hypothetically possible for any nation – indeed, the UK’s failure to deliver an investment strategy has been a point of longstanding frustration. Whether it’s chemical and materials, the development of IP and components, the manufacturing of equipment, or the actual production of chips, there are a whole host of niches that countries can pursue in order to guarantee their voice at the table.

But the success of that investment goes beyond funding. You need the right environment for businesses to thrive.

Playing politics

The political rhetoric surrounding investment in semiconductors continues to reflect the twin themes of self-sufficiency and national security. With huge amounts of money being deployed, politicians need to be seen to understand and care about the semiconductor space – which leads to bullish catchphrases, and a tendency to act tough toward one’s rivals.

China, for example, is often positioned as a security threat. Despite the reality that entire nations depend on trade with China for profitability, the prevailing sentiment is that opening yourself up to business with China risks an invasion of spyware. Rishi Sunak has said, for example, that China “poses a systemic challenge to our values and interests… that grows more acute as it moves towards even greater authoritarianism.”

However, policies intended to ease supply chain and national security concerns are being applied far too generally. For the companies involved in the IoT (Internet of Things) – as opposed to those developing server-side systems, and the advanced computing that might be deployed nefariously – there’s a frustratingly unnecessary impact upon our business that threatens our ability to remain competitive on a global stage.

Conversations between leaders of state are all-inclusive, failing to reflect the diversity of the semiconductor market. There’s a need, ultimately, to move these discussions away from the politicians and towards the experts who understand the nuance.

A failure to do so perpetuates a lack of specificity and slows our progress – as the UK is currently experiencing with the stasis surrounding Newport Wafer. With far less investment capital to deploy, we must be smarter than those that content themselves with chest-thumping and sabre-rattling – we must pragmatically and thoughtfully deploy our resources where they can make the most impact, and deliver the most leverage on the global stage.