Next-generation drug testing on chips

Improvements to tiny body-on-a-chip devices could lead to next-generation pre-clinical testing of drug toxicity

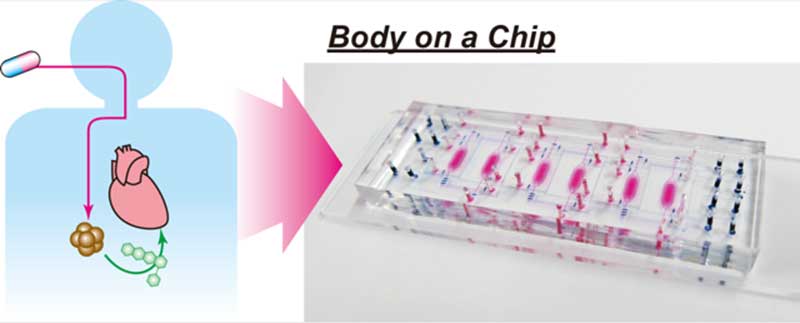

Researchers at Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) in Japan have designed a small "˜body-on-a-chip' device that can test the side effects of drugs on human cells. The device solves some issues with current, similar microfluidic devices and offers promise for the next generation of pre-clinical drug tests

The Integrated Heart/Cancer on a Chip (iHCC) was used to test the toxicity of the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin on heart cells. The researchers, led by iCeMS's Ken-ichiro Kamei, found that, while the drug itself was not toxic to heart cells, a metabolite of the drug resulting from its interaction with cancer cells was.

The device is smaller than a microscope glass slide. It contains six tiny chambers; every two are connected by microchannels with a series of port inlets and valves. A pneumatic pump controls movement of fluid through the channels. Every two chambers and their separate microchannel system constitute one test bed. Three test beds in the device allow for the introduction of minor changes in each bed to simultaneously compare results.

The team first tested doxorubicin's effects on heart cells and liver cancer cells cultured separately in small wells. The drug had the expected anti-cancer effect on the cancer cells without causing damage to the heart cells.

They then ran the test using the iHCC device. Heart cells were placed in one chamber while liver cancer cells were placed in the other. Doxorubicin was introduced into a cell culture medium circulating through a closed-loop system of microchannels that connects the two chambers, mimicking the blood's circulatory system. In this way, the drug flows unidirectionally in a continuous loop through both chambers.

The team found signs of toxicity in both cancer and heart cells. They hypothesized that a compound, doxorubicinol, which is a metabolic byproduct of doxorubicin interacting with cancer cells, was causing the toxic effect.

To test this, they added doxorubicinol to heart cells and liver cancer cells cultured separately in small wells. It was toxic to the heart cells but not to the cancer cells.

When doxorubicin alone is added to the liver cancer cells, the amount of doxorubicinol produced is too small to be toxic to the heart cells. The team believes this is because the amount of cell culture medium needed for the well-based tests dilutes the metabolite.

In contrast, when doxorubicin is introduced into the iHCC, the metabolite is not diluted when moving through the microchannel circulation system because a smaller volume of cell culture is needed. As a result, the drug does have a toxic effect on the heart cells via its metabolite.

The device requires further improvements, but the study demonstrates how this design concept could be used to investigate the toxic side effects of anti-cancer drugs on heart cells well before expensive clinical trials. The study was published in the journal Royal Society of Chemistry Advances.