Scientists develop tiny tooth-mounted sensors to track what you eat

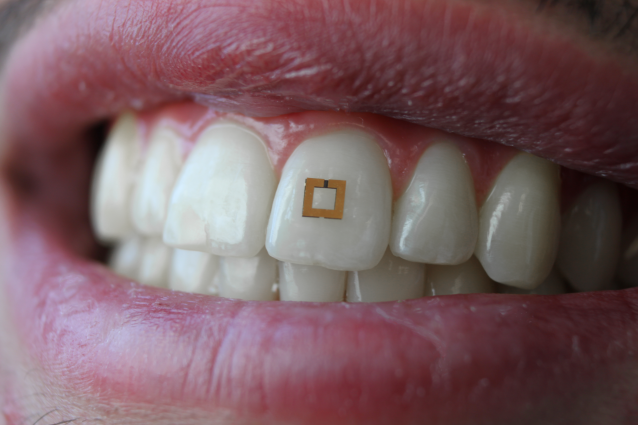

A miniaturized sensor mounted on a tooth. Photo: SilkLab, Tufts University

Monitoring in real time what happens in and around our bodies can be invaluable in the context of health care or clinical studies, but not so easy to do. That could soon change thanks to new, miniaturized sensors developed by researchers at the Tufts University School of Engineering that, when mounted directly on a tooth and communicating wirelessly with a mobile device, can transmit information on glucose, salt and alcohol intake. In research to be published soon in the journal Advanced Materials, researchers note that future adaptations of these sensors could enable the detection and recording of a wide range of nutrients, chemicals and physiological states.

Previous wearable devices for monitoring dietary intake suffered from limitations such as requiring the use of a mouth guard, bulky wiring, or necessitating frequent replacement as the sensors rapidly degraded. Tufts engineers sought a more adoptable technology and developed a sensor with a mere 2 mm x 2 mm footprint that can flexibly conform and bond to the irregular surface of a tooth. In a similar fashion to the way a toll is collected on a highway, the sensors transmit their data wirelessly in response to an incoming radiofrequency signal.

The sensors are made up of three sandwiched layers: a central "bioresponsive" layer that absorbs the nutrient or other chemicals to be detected, and outer layers consisting of two square-shaped gold rings. Together, the three layers act like a tiny antenna, collecting and transmitting waves in the radiofrequency spectrum. As an incoming wave hits the sensor, some of it is cancelled out and the rest transmitted back, just like a patch of blue paint absorbs redder wavelengths and reflects the blue back to our eyes.

The sensor, however, can change its "color." For example, if the central layer takes on salt, or ethanol, its electrical properties will shift, causing the sensor to absorb and transmit a different spectrum of radiofrequency waves, with varying intensity. That is how nutrients and other analytes can be detected and measured.

"In theory we can modify the bioresponsive layer in these sensors to target other chemicals "“ we are really limited only by our creativity," said Fiorenzo Omenetto, Ph.D., corresponding author and the Frank C. Doble Professor of Engineering at Tufts. "We have extended common RFID [radiofrequency ID] technology to a sensor package that can dynamically read and transmit information on its environment, whether it is affixed to a tooth, to skin, or any other surface."

Other authors on the paper were: Peter Tseng, Ph.D., a post-doctoral associate in Omenetto's laboratory, who is now assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at University of California, Irvine; Bradley Napier, a graduate student in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Tufts; Logan Garbarini, an undergraduate student at the Tufts School of Engineering; and David Kaplan, Ph.D., the Stern Family Professor of Engineering, chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, and director of the Bioengineering and Biotechnology Center at Tufts.

The work was supported by U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, the National Institutes of Health (NIH; F32 EB021159) National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and the Office of Naval Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center, or the Office of Naval Research.