Harvesting hydrogen from sunlight with porous silicon

Scientists also see applications for batteries, biosensors and optical electronics as outlets for this new material

Porous silicon manufactured in a bottom up procedure using solar energy can be used to generate hydrogen from water, according to a team of Penn State mechanical engineers.

The surface area of this porous silicon is high," according to Donghai Wang, assistant professor of mechanical engineering. "It is widely used and has a lot of applications."

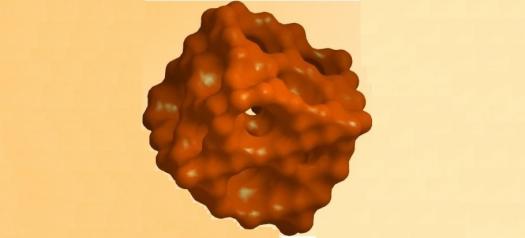

A schematic of porous silicon is shown at the top of this article. (Credit : Donghai Wang, Penn State)

The standard method for manufacturing porous silicon is a subtraction method, similar to making a sculpture.

"Silicon is an important material because it is a semiconductor," notes Wang. "Typically, porous silicon is produced by etching, a process in which lots of material is lost."

Wang's team uses a chemically based method that builds up the material rather than removing it. The researchers start with silicon tetrachloride, a very inexpensive source of silicon. They then treat the material with a sodium potassium alloy.

"The bonds between silicon and chlorine in silicon tetrachloride are very strong and require a highly reducing agent," explains Wang. "Sodium potassium alloy is such an agent."

A micrograph of mesoporous silicon with sodium chloride and potassium chloride salts embedded in the matrix. (Credit: Donghai Wang, Penn State)

Once the bonds break, the chlorine binds with the sodium, potassium and silicon, potassium chloride and sodium chloride - table salt - become solid, forming a material composed of crystals of salt embedded in silicon. The material is then heat-treated and washed in water to dissolve the salt, leaving pores that range from 5 to 15 nanometres. The researchers report their results in the April 10th issue of Nature Communications.

Because the sodium potassium alloy is highly reactive, the entire procedure must be done away from the oxygen in the air, so the researchers carry out their reaction in an argon atmosphere. "I believe that the process can be scaled up to manufacturing size," says Wang. "There are some processes that use sodium potassium alloy at industrial levels. So we can adapt their approaches to make this new type of porositic silicon."

A TEM micrograph of mesoporous silicon showing holes where salts were removed. (Credit: Donghai Wang, Penn State)

Because these silicon particles have lots of pores, they have a large surface area and act as an effective catalyst when sunlight shines on this porous silicon and water. The energy in sunlight can excite an electron that then reduces water, generating hydrogen gas. This process is aided by the material's larger-than-normal band gap, which comes from the nanoscale size of the silicon crystallites.

"This porous silicon can generate a good amount of hydrogen just from sunlight," Wang concludes.

The researchers are also looking into using this porous silicon as the anode in a lithium ion battery.

This work has been published in the paper, "Bottom-up synthesis of high surface area mesoporous crystalline silicon and evaluation of its hydrogen evolution performance," by Fang Dai et al in Nature Communications, 5, Article number: 3605, published 10th April 2014. doi:10.1038/ncomms4605

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140410/ncomms4605/full/ncomms4605.html

The U.S. Department of Energy and the Defence Threat Reduction Agency funded this work.